The NFL was founded way back on September 17, 1920, in Ralph Hay’s Hupmobile auto showroom by owners and representatives of 10 teams. Four more teams ended up joining the league, making the NFL original teams tally up to 14 for the league in the first season.

This was a big deal, because believe it or not, Pro Football played second fiddle (if that) to College Football during the early parts of the 20th century. It was difficult to maintain order for the professional ranks, thus the need for this league.

And what better way to celebrate the NFL’s 100th birthday than to go back and relive the stories of the original teams? That’s what this week’s episode of The Football History Dude has in store for you. We also have the “Knights of Football History” roundtable to share the origin of each team.

You should listen to the full episode, but also below is even more information provided by the football history experts in “The Ultimate Guide to the NFL Original Teams.”

I highly recommend you use this table of contents hovering at the top of your page to go back and forth between the team and expert you’re interested in learning more about.

Take My DeLorean Back In Time

This time as we step off the Delorean, the date is November 6th, 1869, in New Brunswick, New Jersey to witness a very special event. On this day, about 100 spectators witnessed history. Rutgers took on New Jersey (later the name changed to Princeton).

The game? Well, this is where it gets good, because this was the first American football game to be played. Now, it didn’t look anything like it does today, but it was a start.

During the early days it was still basically rugby, and it would remain the same for roughly the next 7 years. Then, the man we talked about in the very first episode of this podcast got involved.

His name was Walter Camp, aptly referred to as the Father of American Football, for his contributions to changing the game away from rugby/soccer to more of a resemblance of what we watch today. Of course, it still looked way different than what we are used to seeing nowadays. But we were on our way.

Over the next decade and a half, Walter Camp and his buddies continued to evolve the game to something we are more familiar with. Then, on November 12th, 1892, everything changed. This is when the subject of the 2nd episode of the podcast was paid $500 by Allegheny Athletic Association to play a game of football against the Pittsburgh Athletic Club.

The man’s name was William “Pudge” Heffelfinger, a standout at Yale. Thus, becoming the first known player to be paid to play football, but it wasn’t realized he was the true first until about 80 years or so after the event. This is because in 1895, John Brallier was the first openly paid player.

We found out in a few episodes ago from Joe Horrigan how it was found out to be Pudge and not Brallier. Go back and listen. It was an interesting conversation.

Then a few years later a team was formed, which brings us to the point where I’m going to tell you about the special episode we have for you. We gathered experts for sort of a roundtable, if you will, to discuss the original teams of the NFL.

The reason? Because tomorrow we celebrate the 100th birthday of the NFL, which if you’re listening to this in the future, the NFL’s birthday is September 17th, and the league will be 100 years old this year (which is 2020).

The reason why we bring up September 17th is due to an event that happened in 1920 when Ralph Hay brought together other owners in his Hupmobile auto showroom to finalize the formation of what would end up becoming the National Football League. We covered this in depth in a couple different episodes, as well, but what we’re going to do this week is beyond that.

So sit back, strap on your seat belt, and get ready for the wild ride before you. This is “The Ultimate Guide to the Original NFL Teams.”

Akron Pros : By Ken Crippen

Ken is the president and former executive director of the Professional Football Researchers Association. He has been researching and writing about pro football history for over twenty years. In that time, he has published two books and numerous articles. He has also won multiple writing awards, the latest being the 2012 PFWA Dick Connor Writing Award for Feature Writing. In 2011, he was awarded the Ralph Hay award by the PFRA for lifetime achievement in pro football history. His writing has been featured on National Football Post, Cold Hard Football Facts, The Packer Report, and Coffin Corner. I have also appeared on Fox Sports Radio, ESPN Radio, and WGR (Buffalo). More on Ken in episode 121.

Akron Pros - The NFL's First Champion

It’s time to dig deep into the archives to talk about the first National Football League (NFL) champion. In fact, the 1920 Akron Pros were champions before the NFL was called the NFL. In 1920, the American Professional Football Association was formed and started to play. Currently, fourteen teams are included in the league standings, but it is unclear as to how many were official members of the Association.

Different from today’s game, the champion was not determined on the field, but during a vote at a league meeting. Championship games did not start until 1932. Also, there were no set schedules. Teams could extend their season in order to try and gain wins to influence voting the following spring. These late-season games were usually against lesser opponents in order to pad their win totals.

Peggy Parratt Comes to Town

To discuss the Akron Pros, we must first travel back to the century’s first decade. Starting in 1908 as the semi-pro Akron Indians, the team immediately took the city championship and stayed as consistently one of the best teams in the area. In 1912, “Peggy” Parratt was brought in to coach the team.

First "Legalized" Forward Pass

George Watson “Peggy” Parratt was a three-time All-Ohio football player for Case Western University. While in college, he played professionally for the 1905 Shelby Blues under the name “Jimmy Murphy,” in order to preserve his amateur status.

It only lasted a few weeks until local reporters discovered that it was Parratt on the field for the Blues. When brought before the university’s Athletic Board, Parratt admitted his wrong-doing and was subsequently barred from all intercollegiate play. He was the first college star to be disciplined by his school for playing professional football.

He finished the 1905 season with the Lorain Pros before he moved on to the Massillon Tigers in 1906. That year, October 25 specifically, Parratt threw a pass to Dan “Bullet” Riley. That is considered by some to be the first forward pass in a professional football game. Parratt continued his pro football career with the Franklin Athletic Club before he returned to the Blues as player-coach-manager in 1908.

In 1909, the Blues tied the Akron Indians for the state championship and won it outright in 1910. Shelby would again see themselves in the championship game in 1911, this time against the Canton Pros. A disputed offside ruling during the game angered Canton to the point of forfeiting. Parratt joined the Akron Indians in 1912 and immediately changed their name to Parratt’s Indians, but the little known Elyria Athletics took the championship.

Parratt immediately set out to raid the champion Elyria roster and brought back the 1913 crown after a 9-1-2 season. They repeated as champions in 1914 with an 8-2-1 record. Of note during that season, in their November 15 matchup with the Canton Pros, Akron fullback Joe Collins tackled center, Harry Turner, breaking his spine and severing his spinal cord. He died a short time later.

Akron’s roster was decimated in the offseason.

The Massillon Tigers and Canton Bulldogs stole the bulk of Parratt’s players and the 1915 season was a disaster for Parratt. Going 1-4-2, including four games played as the Shelby Blues, was enough for Parratt and he left to head up the Cleveland Tigers.

1916: Leading Up to the NFL

The 1916 squad was reorganized by Howe Welch, footballer out of Case, and brothers “Suey” and “Chang.” The Akron squad also picked up a sponsor in the Burkhardt Brewing Company, namely Gus and Bill Burkhardt. The team was renamed the Akron Burkhardts and went 7-4-1 for the season. However, that sponsorship only lasted one season as Stephen “Suey” Welch and Vernon “Mac” McGinnis bought the team and renamed them the Akron Pros.

Welch and McGinnis brought in Al Nesser, the youngest of the seven Nesser brothers that played for the Columbus Panhandles between 1904 and 1922. Alfred “Al” Louis Nesser did not play college football but started immediately in the pros with the Columbus Panhandles in 1910.

He stayed on and off with the team through 1919, with stops on the Canton Bulldogs, Massillon Tigers, as well as the Akron Pros. The 1917 incarnation of the Akron team went 6-2-0 before temporarily disbanding during World War I. They retook the field in 1919 as the Indians, with “Suey” Welch out and Ralph “Fat” Waldsmith, Art Ranney, and Park “Tumble” Crisp joining McGinnis as owners. Waldsmith played for the Indians in 1914 and the Canton Bulldogs in 1916. Crisp played for Canton in 1916 and Akron in 1917.

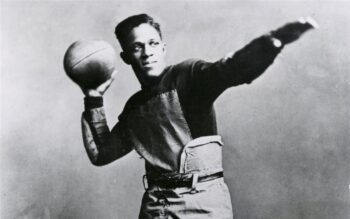

The new owners brought in halfback Fritz Pollard, who was one of the first African-Americans (along with Bobby Marshall) to play in the NFL in 1920. Frederick Douglass “Fritz” Pollard played his college football at Brown University. He graduated in 1919 and joined the Akron Indians to start his professional career.

New Owners

After the 1919 season, the team was sold to Art Ranney, an Akron businessman and former player for Akron University, and cigar-store owner Frank Neid. The Indians’ name was sold to “Suey” Welch, who fielded a team in 1921. Welch later became a successful boxing promoter and was inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame. His brother Charles “Chang” Welch also became a boxing promoter.

A New League on the Horizon

Even though it had been attempted previously, 1920 saw yet another push to form a professional football league. Teams in the mythical “Ohio League” saw clubs from other parts of the country draw more fans to the games, which obviously translated to increased revenue for the teams participating.

The fear was that more talented players would be drawn away from the smaller Ohio towns to other cities in search of larger salaries. Something needed to be done to keep the Ohio teams on a competitive level with organizations from outside of the Buckeye state.

The first step was taken on August 20, 1920, when four of the Ohio League teams met at Ralph Hay’s Hupmobile dealership in Canton, Ohio. Hay owned the Canton Bulldogs and was joined by his star player Jim Thorpe. Also at the meeting were Frank Nied and Art Ranney of Akron, Jimmy O’Donnell and Stanley Cofall of the Cleveland Tigers, and Carl Storck of the Dayton Triangles.

Since no minutes were recorded for this meeting, the final outcome is a bit of a mystery, but a few things could be ascertained from media accounts of the event. First, the name of their new “league” was to be called the American Professional Football Conference, and Hay was elected Secretary. Now, the focus could shift to the major issues facing those teams. Players were running from team to team to collect a paycheck.

The members wanted this to stop and agreed to refrain from enticing players to leave their current club. Next, they needed to get player salaries under control, so they introduced a salary cap. Finally, they needed to address the increasing row between colleges and professional clubs with respect to undergraduate players. Colleges increasingly frowned on their players involving themselves in professional contests.

The members of the league agreed to not allow these undergraduates to play on their squads. With that, all of the major issues addressed, they needed to get outside clubs to join and agree to the aforementioned stipulations.

Would All the Hard Work Be Forgotten?

All of the work that came out of the meeting would be for naught if only the four attending clubs were members of the league. They needed to bring in the organizations they most feared would induce their players to leave.

Hay was responsible for contacting top-notch professional clubs in the surrounding states to have them attend the next meeting. Before that, however, the league received letters from three clubs, expressing interest in joining. The first was from Leo Lyons of the Rochester Jeffersons.

Actually, it is not absolutely certain that the letter was from the Jeffersons, but since they were by far the strongest Rochester team, it can be assumed that it was from the Jeffersons. Couple that with the fact that Leo Lyons attended the follow-up meeting to the August 20th affair, it is safe to say that the letter was from the Jeffersons.

Leo had always pushed for a league and when he heard that there was the possibility of one forming, it is assumed that he jumped at the chance to participate and sent the letter. The second letter was from Buffalo. Again, since no meeting minutes were recorded, there is no way to be absolutely certain who wrote the letter, but it is assumed that it was the Buffalo All-Americans, who were essentially the 1919 Buffalo Prospects under new management.

The third letter was from Hammond, but it is unclear as to which Hammond team sent the letter. The Hammond Pros attended the second league meeting, but the Hammond Bobcats were also a strong contender in the area. The answers to these questions remain to this day.

A New League is Born

The second league meeting was held on September 17, 1920, in Canton. Hay and Thorpe were there, along with previous attendees Nied, Ranney, Storck, Cofall, and O’Donnell. New to the meeting were Leo Lyons of the Rochester Jeffersons, Doc Young of the Hammond Pros, Walter Flanigan of the Rock Island Independents, Earl Ball of the Muncie Flyers, George Halas and Morgan O’Brien of the Decatur Staleys, and Chris O’Brien of the Chicago Cardinals.

One of the first items to come out of this meeting was to change the name of the league to the American Professional Football Association (APFA). Next up was to choose the leadership. Jim Thorpe was elected as president, Stanley Cofall was elected vice-president and Art Ranney took the secretary-treasurer position.

With the leadership in place, they could now get down to the details. Young, Flanigan, Storck, and Cofall were responsible for drawing up a constitution and bylaws. It was also decided that each team would provide a list of all players used during the 1920 season and that this list was to be provided to Art Ranney (Association Secretary) by January 1, 1921.

This was in reference to teams enticing players to jump teams, the only of the three items that actually addressed the reasons why the league was formed. The league was shaped up as follows: Akron Pros, Buffalo All-Americans, Canton Bulldogs, Chicago Cardinals, Chicago Tigers, Cleveland Tigers, Columbus Panhandles, Dayton Triangles, Decatur Staleys, Detroit Heralds, Hammond Pros, Muncie Flyers, Rochester Jeffersons, and Rock Island Independents.

All that was left was to play the games. Of note, the official meeting minutes of the first league gathering were kept on Akron Pros stationary.

Akron Pros and the First NFL Season

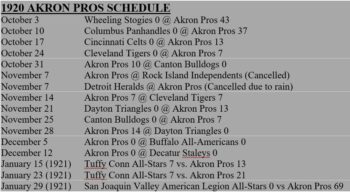

The Akron Pros opened their 1920 season by playing the non-league Wheeling Stogies. End Al Nesser scored the first three touchdowns – two fumble recoveries and a blocked kick recovery – and back Fritz Pollard added two on end runs. Back Harry Harris finished the scoring with a fourth-quarter touchdown to seal the 43-0 victory.

In the sweltering heat, Akron continued their winning ways by beating the Columbus Panhandles 37-0. Akron seemed to gain yardage at will, while the visitors struggled to drive the ball. Fullback Frank McCormick started the scoring with a three-yard dive through the Columbus line and again scored to give Akron a 14-0 lead. Harry Harris, Bob Nash, and Fred Sweetland scored touchdowns, and end Scotty Bierce tackled Frank Nesser for a safety to finish the scoring.

Akron continued their home stand by taking on the visiting non-league Cincinnati Celts. The game was not as close as the 13-0 final score indicated. Akron seemed to drive the ball with ease, while Cincinnati did not register a first down. Tailback Rip King scored approximately five minutes into the game to give Akron a 7-0 lead, while Fritz Pollard clinched the victory with a touchdown run in the final period. Scoring would have been higher, but Akron missed on three field-goal attempts.

Next up for Akron was the visiting Cleveland Tigers. The Pros racked up twelve first downs in the game, but it took a freak play to put points on the board for the home team. In the first quarter, tailback Stanley Cofall dropped back to punt for the Tigers. As the ball was snapped, Bob Nash streaked through the line, caught the ball as it was punted, and raced the final eight yards for a touchdown. Even though Akron was able to move the ball, the Cleveland defense held firm as Akron approached the goal line.

The final score was 7-0 to preserve Akron’s undefeated streak. Ten thousand fans saw Akron dismantle the perennial powerhouse Canton Bulldogs on October 31. Coming off their first loss since 1917, the Bulldogs were expected to rebound on their home field, but the Akron squad was too much. In the first quarter, Charlie Copley put Akron on the board with a 38-yard field goal.

The legendary Jim Thorpe entered the game in the third quarter and Canton showed some signs of life. However, a strong defensive effort by Akron prevented Canton from crossing the Pros’ ten-yard line. Canton tailback Joe Guyon returned Rip King’s punt to midfield. Johnny Gilroy dropped back to pass, but Bob Nash and Pike Johnson split the line and blocked Gilroy’s pass. Johnson caught the deflection and ran 50 yards for the touchdown. Canton’s only chance to score came in the third quarter when Thorpe failed to kick a field goal from the Akron 18-yard line.

Akron traveled to Cleveland for their second road game of the season. Two weeks prior, the Pros beat Cleveland 7-0, but the Tigers wanted revenge. To this point in the season, Akron was undefeated, untied and gave up no points to their opposition. The Pros wanted to keep that streak alive. It started with two beautiful twenty-yard runs by tailback Fritz Pollard to give Akron a 7-0 lead in the second quarter. In the third quarter, Cleveland struck. Back Mark Devlin hoisted a 25-yard pass to tailback Tuffy Conn, who raced 25 yards for a touchdown to tie the game.

These were the first points scored against Akron all season. The game ended in a 7-7 tie, breaking Akron’s undefeated – untied record. The following week saw Akron take on the 4-0-2 Dayton Triangles. Dayton’s defense held for the first three quarters, but Akron broke free in the final period. Rip King passed to Frank McCormick for a touchdown to break the scoreless deadlock. Soon after, Fritz Pollard ran around end for a 17-yard scoring scamper to give Akron a 13-0 victory.

At this point in the season, the Akron Pros were 6-0-1 and ready to face a rematch with the 6-1-1 Canton Bulldogs. With only a few days rest after the win over Dayton and an undefeated season still in play, the Pros could not afford a letdown against the championship-contender Bulldog team. Even though Akron beat Canton earlier in the season, there was an unwritten rule that with tie-breakers, second games count more than the first when it came to the final standings.

Canton made a costly mistake in the first quarter. Canton quarterback Tex Grigg fumbled an Akron punt and end Scotty Bierce fell on it to give the ball to the Pros at the Canton 32-yard line. A pass from Rip King to Bierce put the ball on the Canton twelve-yard line and a pass from King to Bob Nash gave Akron a 7-0 lead. After that, Akron’s defense took charge and Canton was unable to score. In two games, Akron held Canton scoreless and preserved their undefeated streak.

Next, Akron faced a rematch with the 5-1-2 Dayton Triangles. The only loss for the Triangles was against the Pros. It was a hard-fought match, but Akron took charge in the second half. With Dayton quarterback Al Mahrt going down to a broken collarbone, the Triangles’ offense sputtered. In the third quarter, Rip King received a Dayton punt but fumbled the ball around midfield.

Fritz Pollard recovered the loose ball and weaved his way to the goal line for the first score of the game. In the fourth quarter, Akron’s offense drove to the Dayton 20-yard line. A fumble and two penalties pushed the Pros back to the Triangle 32-yard line. On the next play, King dropped back to pass but was hit by tackle Max Broadhurst. King fell to one knee, but the play was not over. King got up and tossed a pass to Pollard for a score and a 14-0 victory. That essentially eliminated Dayton from championship consideration, while the 8-0-1 Akron Pros were on their way to a title.

Around December 5, 1920, the Akron Pros sold end/tackle Bob “Nasty” Nash to the Buffalo All-Americans for $300 and five percent of the gate receipts for their game with the All-Americans. That was considered the first player transaction in league history. However, Nash did not suit up for either team in their December 5 matchup.

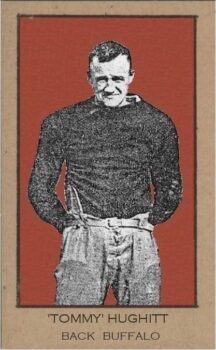

Only 3,000 fans showed up in the Buffalo winter weather. Intermittent rain and snow, combined with a blustery wind made things difficult for both teams. However, late in the second quarter, Akron’s offense provided a spark. Five straight first downs put the ball on the Buffalo two-yard line, but the defense of the All-Americans held on downs. Akron again drove to the shadow of the Buffalo goal in the fourth quarter, when Rip King tossed a pass to end Al Nesser, who rumbled his way to the one-yard line. Buffalo back Tommy Hughitt stopped Nesser short of the goal.

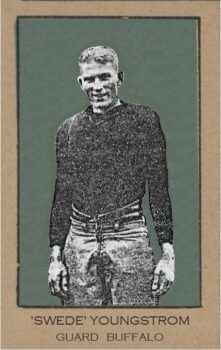

Near the end of the game, Hughitt dropped back to punt from his goal line. His punt went about five yards, but with an Akron man touching it and failing to recover the loose ball, Buffalo’s Bodie Weldon fell on it to regain possession for the All-Americans. A poor pass by Lud Wray almost caused Buffalo guard Swede Youngstrom to fall back into his own goal for safety. That was the last scoring opportunity for either team. The game ended in a scoreless tie.

With only one game remaining, 8-0-2 Akron needed to beat the 10-1-1 Decatur Staleys to leave no doubt as to the first champion of the APFA. Decatur did not leave anything to chance and hired Chicago Cardinal tailback, Paddy Driscoll. However, even with all of the stars on the Staley team, neither team was able to put points on the board. Akron’s offense had a slight advantage in yards, but the Staleys drove deeper into Akron territory. Obviously, without points to show for their efforts, it really did not matter.

The champion would be determined by a vote of the membership, with Akron and Decatur both claiming the title. The two teams had to wait until April 30, 1921, to see who would take home the crown.

That marked the end of the first year of the APFA.

Even with their best efforts, the league was not able to stop the three things that forced them to create the Association in the first place: skyrocketing salaries, team jumping, and the use of college undergraduates. In fact, it was as if the Association did not even exist. The end of the 1920 season still called for the formation of a pro football league, even by members of the Association!!

Regardless, the APFA decided to continue and had a meeting on April 30, 1921. Thorpe and Cofall did not attend, so Art Ranney took charge. Other attendees included Joe Carr, Leo Conway (Union Athletic Association), George Halas, Ralph Hay, Lester Higgins (brother-in-law of Hay), Charles Lambert, Leo Lyons, Frank McNeil, Frank Nied, Chris O’Brien, Morgan O’Brien, Carl Storck, and Doc Young.

A Champion is Crowned

First on the agenda was to vote for the “champion” of the association. Carr nominated the Akron Pros and it was approved. Akron was able to rack up an impressive unbeaten 8-0-3 record, playing tough opponents. That is what carried them to the “championship,” even though Decatur tied Akron (and thought that would be enough to get them the championship) and Buffalo tied Akron and beat Canton.

Regardless, Akron won the championship based on the vote of the membership. The Pros were awarded a loving cup from the Brunswick-Balke Collender Company. Unfortunately, the cup has been lost to history, as its current location is a mystery. It has never been mentioned or seen since.

The next item on the meeting agenda was the appointment of a new leader. After a short discussion, Joe Carr was elected the new Association president, replacing Jim Thorpe. Morgan O’Brien was elected vice-president and Carl Storck secretary-treasurer.

Making good on the promise from the previous meeting, members of the Association had until May 15th to submit a list of all players that played on their squad the previous season. These players were not allowed to be enticed into leaving until the club management released them from their contract. This was to address the team-jumping issue that plagued clubs of that era. Finally, the Association was taking a hard stand to clean up the sport.

Another point that needed to be addressed was players playing for more than one team in the same week. This hit home with Conway and McNeil, as both teams were guilty of this practice.

McNeil’s Buffalo All-American players suited up for Conway’s Union team on Saturdays and then returned to Buffalo to play for the All-Americans on Sunday. This was pretty much overlooked up to this point, but the situation would boil toward the end of the 1921 season. Another Association meeting occurred on June 18, 1921, at the Hollenden Hotel in Cleveland.

The main purpose of this meeting was to start establishing schedules and to approve a new constitution (it looked like one was never written, as promised in the 1920 meetings). Rochester’s Leo Lyons never attended this meeting, but representatives from Akron, Buffalo Canton, Chicago, Columbus, and Dayton all made the trip. There is no official record of Buffalo ever being admitted to the Association in 1920, but it was brought up at this meeting.

Also attaining membership at this meeting was Cleveland, Detroit, Rock Island, and Toledo. Even though Rock Island was a member in 1920, there seemed to be an issue with whether they were still members at the end of the 1920 season. It is unclear as to the exact reason, but the Independents played a team from Washington and Jefferson at the end of the season, a frowned-upon offense.

As if the first two meetings were not enough, a third meeting was held on August 27, 1921, at the LaSalle Hotel in Chicago. Leo was able to make it to this meeting, which also included members of the Akron, Buffalo, Canton, Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Dayton, Decatur, Detroit, Evansville, Fort Wayne, Green Bay, Louisville, Minneapolis, Rock Island, and Toledo squads. Coming out of this meeting was an agreement that any organization receiving a request to have a college player suit up for their team, must notify university officials.

There are no records showing that any club followed through with this agreement. Also, Buffalo was officially admitted to the Association, along with Minneapolis, Evansville, Tonawanda, and Green Bay. The Washington Senators and Brickley’s New York Giants were not admitted at this meeting but were admitted before the beginning of the season.

Beyond the Championship Season

For the 1921 season, Fritz Pollard became co-head coach with 1920 head coach Elgie Tobin, becoming the first African-American head coach in NFL history. With an 8-3-1 record, they again made a run for the league championship but fell just short of the 9-1-2 Chicago Staleys (formerly the Decatur Staleys and would be named the Chicago Bears the following season) and the 9-1-1 Buffalo All-Americans.

In 1922, the American Professional Football Association changed its name to the National Football League. The Akron Pros started to fall apart in 1922, only going 3-5-2 that year, 1-6-0 in 1923, and 2-6-0 in 1924. They saw a slight improvement in 1925, finishing fourth in the league with a 4-2-2 record, but fell apart in 1926, only winning one of eight games as the newly renamed Akron Indians.

The National Football League was going through some difficulty by 1927. The feud with the rival American Football League (AFL) had a financial impact on NFL franchises. As they tirelessly worked to prevent the AFL from getting any foothold and quickly expanded to compete in every AFL city, they subsequently weakened their own league. Something needed to be done. The weaker franchises were dragging down the stronger clubs, preventing them from making a profit.

Blueprint For Akron's Demise

February 5, 1927, was the date of the first league meeting to discuss what to do to strengthen the NFL. The AFL was pretty much history, so the focus of the owners shifted internally to the league. Clubs like Rochester, Akron, and Canton were not strong enough to draw the crowds necessary for the bigger clubs to succeed.

The league meeting would start with Dr. Harry March requesting that a committee be formed to design a reorganization plan. NFL Commissioner Joe Carr appointed representatives of the Chicago Bears, New York Giants, Frankford Yellowjackets, Kansas City Cowboys, Akron Indians, Columbus Tigers, Providence Steamroller, Pottsville Maroons, and Green Bay Packers to this committee, with Charles Coppen of the Providence Steamroller being named chairman.

Chairman Coppen reported back that the league should be divided up into two distinct sections: an “A” section and a “B” section. The “A” teams were the strongest teams in the league, while the “B” members were the weakest. This plan immediately drew the ire of the teams labeled under “B” and the meeting was adjourned to discuss other alternatives.

When the meetings the following day got back around to reorganization, chairman Coppen was still unable to put forth a plan that was agreeable by the membership. The “A” and “B” concept would eventually be accepted, but the method of determining who belonged into what classification was still to be completed. Coppen was again appointed to find a solution to this problem and he enlisted the help of Shep Royle of the Frankford Yellowjackets, Johnny Bryan of the Milwaukee Badgers, Jim Conzelman of the Detroit Panthers, and Jerry Corcoran of the Columbus Tigers. The committee came back with the following designations:

A: Providence Steamroller, Frankford Yellowjackets, Milwaukee Badgers, Detroit Panthers, New York Giants, Chicago Bears, Chicago Cardinals, Cleveland Bulldogs, Green Bay Packers, Buffalo Bisons, and the Brooklyn Lions with the Duluth Eskimos, Kansas City Cowboys, and Pottsville Maroons relegated to traveling teams.

B: Akron Indians, Canton Bulldogs, Columbus Tigers, Dayton Triangles, Hammond Pros, Hartford Blues, Louisville Colonels, Minneapolis, Racine Tornadoes, and Rochester Jeffersons.

The next item up for discussion was how to dismantle the “B” franchises. Each team was resigned to their fate, but proper compensation needed to be established. Corcoran insisted that the “B” teams sell their franchises back to the league at the current rate of $2500 each. The “A” teams immediately rejected that suggestion. It was now up to Carr to come up with a compromise and the league gave him until April 15 to make that decision.

Carr did not make his plan known until the April 23rd meeting at the Hotel Statler in Cleveland. Most of the “B” franchises did not show. The only representatives for those franchises were men who also held league positions; namely, Jack Dunn (Minneapolis) who was NFL vice-president, Carl Storck (Dayton) who was secretary-treasurer, Aaron Hertzman (Louisville), and Jerry Corcoran (Columbus). They devised a six-point plan:

1) Any franchise that wished to suspend operations for the year may do so without having to pay the requisite dues. Any franchise that wished to sell their franchise back to the league may do so and will receive a pro-rated share of the monies in the league treasury at the time. This would be approximately a couple of hundred dollars.

2) If a club decided to suspend operations for the year, the teams could sell player contracts up to September 15, 1927. If the franchise decided to withdraw from the league, but still wanted to operate independently, the league will respect the rights of the players on that franchise.

3) If several franchises decide to operate independently and form their own league, the NFL would respect the rights of the players and the NFL would offer assistance in the operation and organization of the new league, including playing exhibition games with league members. Since Carr wanted a minor league with a close working relationship with the NFL, this was a pretty good option for him. He would have eliminated the weaker teams from his league, while still having a minor league from which to groom players for the NFL.

4) Any franchise that wished to suspend operations could sell their franchise for the current application fee. The downside was that the new owners needed to be approved by the league. Since the league did not want to expand, this was pretty much a moot point.

5) Any franchise that decided to resign from the league could not associate or participate in any other league without permission from the National Football League. This was to guarantee that the AFL would not come back.

6) Franchises had one year to make a decision before the league took more drastic action.

On July 16th and 17th, the league held another set of meetings to discuss scheduling. Obviously, the first item on the agenda was to determine who would remain in the league and who would resign. Brooklyn sold their franchise to Tim Mara, owner of the New York Giants. Milwaukee operated as an independent franchise. Detroit and Kansas City unloaded their rosters and Minneapolis suspended operations for a year.

The Rochester Jeffersons suspended operations on July 16, 1927, but failed to re-activate or sell the team by the July 7, 1928 deadline indicated in the plan. Therefore, the franchise was canceled. Akron also suspended operations on July 16, 1927, and forfeited their franchise back to the league in 1928.

Buffalo All-Americans: By Jeff Miller

Jeffrey Miller is an award-winning author and resident Buffalo All-American guru, and he stops by the show to tell us the story of the first NFL team in the Queen City. He has even more books on Amazon than what are listed below.

Jeff was in episodes 98 and 99.

A Name That Fits the Queen City

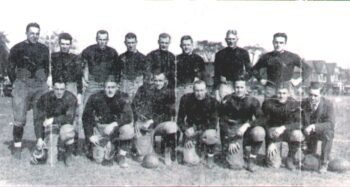

When the American Professional Football Association began play in 1920 (it was renamed the National Football League in 1922) with teams such as the Akron Pros, Canton Bulldogs, Columbus Panhandles, Dayton Triangles, Decatur Staleys, and Rochester Jeffersons, the Buffalo All-Americans were there.

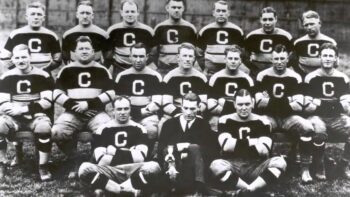

Led by coach/quarterback Tommy Hughitt and a bevy of actual college All-Americans such guard Swede Youngstrom, tackle Lou Little, end Murray Shelton and halfback Ockie Anderson, Buffalo might have had the most aptly named team in the history of the league.

All photos below provided by Jeff Miller.

Joining the New League

The team was an outgrowth of a local semi-pro outfit called the Buffalo Niagaras (named for a Queen City street), who in 1918 had won the Buffalo Semi-Pro Football League title. A year later, the Niagaras’ core players formed a new team, called the Prospects (after another Buffalo street).

The Prospects carried on the tradition of success, taking the New York State championship in its first and only season.

After claiming local and state titles in successive seasons, Buffalo’s gridders were eager to try their luck with the new national league they had read about. Having missed the initial league meetings, a letter requesting membership was submitted to the league founders, and the Queen City’s team was welcomed as a charter member.

Much of the early legwork for the Buffalo team was performed by Howard E. “Barney” Lepper, a former member of both the Niagaras and the Prospects. All of the early press announcements refer to Lepper as the team’s manager, and it was Lepper and local businessman (and Lepper’s eventual successor as team manager) Frank J. McNeil who signed the lease for the team to play their home games at local Canisius College’s open area known as the Villa.

One of the first players signed up was a feisty, 27-year-old quarterback out of the University of Michigan named Ernest “Tommy” Hughitt, a teammate of Lepper’s on the Niagaras and Prospects. After guiding those teams to respective championships, the diminutive Hughitt–all of five feet, eight inches in height and weighing 150 pounds–was the obvious choice to call the signals for the new franchise.

After recruiting such college stars as guard Adolph “Swede” Youngstrom of Dartmouth, halfback Ockie Anderson of Colgate, end Murray Shelton of Cornell, and end Henry “Heinie” Miller and center, Lud Wray of the University of Pennsylvania, the team eventually adopted a most logical nickname, the Buffalo All-Americans.

The All-Americans established themselves as one of the elite teams in the early days of the APFA, finishing within one game of the title in each of the first two seasons of the league. In 1921, the All-Americans actually claimed the title but lost it to the George Halas’ Chicago Staleys in an executive decision.

Papa Bear and an Early League Controversy

They had gone undefeated in their first nine games that year, and after defeating the Dayton Triangles at the old Canisius Villa to end their season on November 27, the All-Americans claimed the league title with a record of 8-0-2. But for some unknown reason, team manager McNeil had scheduled his team to play two more games that, he told local papers, would have no bearing on the team’s claim to the title.

Enter George Halas. Halas’ Staleys (who became the Chicago Bears a year later) had amassed a record of 7-1-0, with their only loss coming against Buffalo on November 24 (Thanksgiving Day). He scheduled a rematch with Buffalo at Chicago for December 4, hoping to exact revenge against the team that had marred his perfect record.

McNeil made the mistake of scheduling his team’s two “post-season” contests on the same weekend, the first for Saturday, December 3, against the tough Akron Pros, after which his men would take an all-night train to Chicago to play the Staleys on Sunday.

After dispatching the Pros on Saturday, the All-Americans were off to Chicago, where they disembarked the next day in no condition to take on Papa Bear’s hungry brutes. The All-Americans fought hard, but the Staleys took the game, 10-7.

McNeil still believed his team was champion, but Halas had other ideas—he argued the title belonged to the Staleys, basing his claim on his belief that the second game of their series with Buffalo mattered more than the first. He also pointed out that the aggregate score of the two games was 16-14 in favor of the Staleys.

McNeil insisted his team’s last two games, including the one against Chicago, were merely exhibitions. It didn’t matter. The league declared the Staleys champions.

McNeil spent the rest of his life arguing that his team had been swindled but was never able to get the league to reverse its decision. Some historians still agree that the title is rightfully Buffalo’s, but it is unlikely the city will ever see the 1921 decision overturned.

All-Americans in the News Long After

The All-Americans enjoyed winning seasons in 1922 and ’23 but never again attained the success they had in those first two years.

McNeil sold the franchise in 1924 to a group led by Warren D. Patterson and Tommy Hughitt, who changed the team name to Bisons. Hughitt lasted one more year before hanging up his cleats. Further changes in ownership and name occurred throughout the decade but to no avail. By 1929, Buffalo’s first professional football team had run out of money and time.

Fast forward nine decades … The Buffalo All-Americans were thrust into the limelight on October 30, 2011, when the San Francisco 49ers tied an obscure record set by the All-Americans in the league’s inaugural season. The record in question was for most games at the start of a season with at least one rushing touchdown scored while not allowing a rushing touchdown. The long-standing record of seven games set by the All-Americans took 91 years to break!

The All-Americans made sports headlines again in 2019 when ESPN announced that the New England Patriots had compiled a startling point differential (points scored versus points given up) of 175 through the season’s first seven games.

The network, however, used a graphic that showed the Pats’ differential was only good enough for second-best in league history. The best? The All-Americans of 1920, who compiled a plus-minus of 218 points through their first seven games! What’s more, the All-Americans of 1921 had the fourth-best differential with 163 points.

George Halas’ Chicago Bears held the third spot with 173.

Canton Bulldogs: By Chris Willis

Chris was on episodes 107 and 108.

Chris Willis is the Head of the Research Library for NFL Films, a position he has held since 1996. He also is an author of 7 books. Chris has been nominated and won Emmy’s for his work on NFL documentaries, including HBO’s Hard Knocks. He was elected in 2018 to the Urbana University Hall of Fame and was also given the Pro Football Researcher’s Association Ralph Hay award for lifetime achievement in the pursuit of preserving the game. Learn more from Chris’ website.

Canton Bulldog Team History

The Canton Bulldogs were a Pro Football team located in Canton, Ohio. The Canton team started playing in the unofficial “Ohio League” from 1902 to 1906 and then 1911 to 1919, as well as in the National Football League from 1920-1923 and again in 1925-1926.

The Bulldogs would go on to win three “Ohio League” championships in four seasons, 1916-1917, 1919. They were also NFL Champions in 1922 and 1923, as the Bulldogs played 25 straight games without a defeat, still an NFL record. As a result of their success, and the NFL’s founding in Canton, the Pro Football Hall of Fame is located there. Jim Thorpe, the Olympian and well-known athlete, was the Bulldogs greatest player.

In 1924, Sam Deutsch, the owner of the NFL’s Cleveland Indians, bought the team and took the Bulldogs name and players with him, naming his team the Cleveland Bulldogs. The Cleveland Bulldogs went on to win the 1924 NFL Championship with a team stocked with former Canton players.

The Canton Bulldogs were re-established in 1925 with new owners and the NFL considers the 1925-1926 Bulldogs to be the same team as the earlier ones (1920-1923).

All photos below provided by Chris Willis.

City of Canton

The City of CANTON is the county seat of STARK COUNTY. The municipality is located in northeastern Ohio and is situated on Nimishillen Creek, approximately 24 miles south of Akron and 60 miles south of Cleveland.

Canton was founded in 1805, incorporated as a village in 1822, and re-incorporated as a city in 1838. Bezaleel Wells, the surveyor who divided the land of the town, named it after Canton (a traditional name for Guangdong Province), China. The name was a memorial to a trader named John O’Donnell, whom Wells admired. O’Donnell had named his Maryland plantation after the Chinese city, as he had been the first person to transport goods from there to Baltimore.

Canton developed into an important agricultural and industrial center due to the Civil War. Canton, along with Akron, emerged as the leading agricultural implement manufacturers in northeastern Ohio in the years leading up to and following the Civil War. Canton also developed as an important center for iron production.

In 1888, Canton’s manufacturing establishments brought in almost five million dollars in income. Machinery produced in Canton’s factories was shipped across the world. Equally important to Canton’s traditional industries during the 1880s was the emergence of watch-making establishments. The two main watch producers in Canton were Hampden Watch Manufacturing Company and the Dueber Watch Case Company. In 1890, these two companies employed over 2,300 people, roughly ten percent of Canton’s population.

Upon arriving in Canton from Connecticut and Cincinnati, Ohio respectively, these two companies merged, remaining in operation until the 1930s.

Canton was the adopted home of President WILLIAM MCKINLEY who until the 1930’s was regarded as one of America’s great Presidents. Born in Niles (just north of Youngstown in the northeastern part of state), McKinley first practiced law in Canton around 1867, and was prosecuting attorney of Stark County from 1869 to 1871.

The city was his home during his successful campaign for Ohio governor, the site of his front-porch presidential campaign of 1896 and the campaign of 1900. Thus a world and a cultural empire first sprung from Canton.

The city originally functioned as a prominent manufacturing center which expanded during the turn of the century due to industrialization and the addition of railroad lines. During the twentieth century, many Canton businesses continued to be iron and steel manufacturers, but other businesses emerged.

- In 1898, HENRY TIMKEN obtained a patent for the tapered roller bearing, (a bearing similar to a ball bearing but using small cylindrical rollers instead of balls) and in 1899 incorporated as The TIMKEN ROLLER BEARING COMPANY in St. Louis. In 1901, the company moved to Canton as the automobile industry began to overtake the carriage industry. Timken and his two sons chose this location because of its proximity to the car manufacturing centers of Detroit and Cleveland and the steel-making centers of Pittsburgh and Cleveland.

In 1917, the company began its steel-and tube-making operations in Canton to vertically integrate and maintain better control over the steel used in its bearings. World War I had created an increase in demand for steel, affecting its supply and price in the market.

At this time the city of Canton had a very popular trolley service, as well as a booming car industry.

Canton marks the halfway point between New York City and Chicago, and the city was a hub for gangsters. During the height of prohibition, Canton earned the nickname of “Little Chicago” (some historians have cited Al Capone for giving the city the nickname).

A mayor and his brother was removed from office, and DONALD RING MELLETT, the editor of the Canton Daily News, spent his short time in Canton calling out the corrupt to account for their misdeeds. On July 26, 1926, he was rewarded for his vigilance with a bullet in the back of the head.

The chief of police was convicted of being involved in the murder, but was later acquitted after a retrial. The former chief of detectives and three local thugs spent the rest of their lives in prison for the murder.

Football Origins

Prior to the debut of Pro Football in the city, an amateur team from Canton was considered as the best team in Stark County. Until about 1902 it competed with the Akron East Ends for the Ohio Independent Championship. When the Massillon Tigers arrived on the scene and went professional, Canton, as an amateur team, was no longer competitive.

The CANTON BULLDOGS were officially established on November 15, 1904 as the CANTON ATHLETIC CLUB, a club designed to operate baseball and football teams. The statement stated that the football team was to be a “professional organization,” complete with a “professional coach.”

Blondy Wallace Comes to Canton

The main goal of the new Canton professional team was to defeat the Massillon Tigers, who had won the “Ohio League” Championship in 1903 and 1904. To do this, Canton recruited several of the best players in the game for more money than what they were getting.

Bill Laub, a player, team captain, and coach of the Akron East Ends, was hired as the team’s first-ever coach.

The team began its 1905 season with a 7-0 record. The Bulldogs then traveled to Latrobe, Pennsylvania to play the Latrobe Athletic Association, led by quarterback John Brallier. Latrobe was not only the current Pennsylvania champions, but had gone undefeated for the last three seasons.

In a tough back-and-forth contest Canton lost 6-0. But the worse part of the setback came when Laub became injured and was unable to finish. BLONDY WALLACE, a former All-American for the Penn Quakers, was named his replacement. Two weeks later Canton lost the Ohio League title to the Tigers, 14-4.

During the 1906 season the team from Canton became known as the “Bulldogs.” Early in November R.C. Johnson, an editorial cartoonist for the Canton Repository drew a picture with a man next to a cub lying in wait for the Massillon Tigers. Suddenly, overnight the team was called the “Bulldogs.”

Wallace began the season by signing several players off the Massillon team, such as Jack Lang, Jack Hayden, Herman Kerchoff, and Clark Schrontz away from the Tigers. Due to the money being spent by Canton and Massillon on professional players, both teams ended up with a spending deficit that had to be shouldered by local businessmen.

That year the Bulldogs won their first game against the Tigers (at Canton), but lost the second game at Massillon. Due to rules of the championship series, the win in the second game allowed Massillon to claim the Ohio championship.

Shortly after the game, a Massillon newspaper charged Wallace with throwing the second contest, to entice Massillon to play a third game to decide the championship.

Canton denied the charges, maintaining that Massillon only wanted to ruin the club’s reputation before the final game against Latrobe. Although Massillon could not prove that Canton had thrown the game, the accusation tarnished Canton’s name and no one attended the Latrobe game.

The scandal nearly ruined pro football in northeastern Ohio. The Canton Morning News put a $20,000 price tag on the 1906 Massillon Tigers team, while many speculate that the Bulldogs probably cost more. While Massillon was still able to field a local team in 1907 (and still won the Ohio League Championship) the Canton team folded.

Bulldogs Return and Jack Cusack Takes Over

In 1911, Canton finally fielded a new team called the Canton Professionals. This would be the first time, but not the last, that the city of Canton showed their resolve by not letting their pro football disappear. The community was now in love with the sport.

That fall the team was made up entirely of local players and the pay was undoubtedly small. In their comeback season, the Pros finished in second place in the “Ohio League” standings behind Peggy Parratt and the Shelby Blues.

In 1912, at the age of 21, JACK CUSACK became the team’s secretary-treasurer, at no cost to the team, as a favor to team captain Roscoe Oberlin. However Cusack was disliked by the current manager H.H. Halter. Cusack later went behind Halter’s back to sign a contract with Peggy Parrett’s Akron Indians, concerning conditions for a match between the two squads, something Halter was unable to do.

When Jack’s actions were discovered by Halter, he tried to dispose of Jack’s services through a team meeting. However during the meeting the team sided with Cusack, after discovering he had secured a 5-year lease on LAKESIDE PARK for the Pros. The result was Halter being removed from the team and Jack being named the team’s new manager.

As manager of the Pros, Cusack slowly added college players to his roster along with the local sandlotters who constituted the bulk of the team. To make the team more profitable he had 1,500 seats added to Lakeside Park. Cusack felt that the Pros had to live down the 1906 scandal and gain the public’s confidence in the honesty of the game.

It was his theory that if he could stop players from jumping from one team to another, it would be a first step in the right direction.

Therefore, several Ohio League managers made a verbal agreement that once a player signed with a team he was that team’s property as long as he played, or until he was released by management – although some pro teams did not abide by this agreement.

In 1914, the Pros challenged Parratt, this time with the Akron Indians, for the Ohio League title. In a game that served as a precursor to the championship, Canton defeated Parratt’s Akron team, however Canton captain HARRY TURNER, was severely injured while attempting to tackle Akron’s Joe Collins. Shortly after the game Turner died of a fracture to his spinal cord.

According to Cusack, who was at Turner’s bedside when he died, his last words were “I know I must go. But I’m satisfied for we beat Peggy Parratt.”

Canton beat Akron 6-0. The death of Turner was taken hard by the team. It was the first fatal accident involving a major professional football team in Ohio. The Canton Pros easily lost a rematch with the Indians a few days later.

The Signing of Jim Thorpe (1915)

Cusack revived the Canton-Massillon rivalry in 1915. With the rivalry, fans began referring to Canton as the “Bulldogs” once again and Cusack reinstated the name. That season Massillon and Canton began hiring bigger name players.

When Canton began the season with a 75-0 victory over a team from Wheeling, West Virginia, the Bulldogs’ starting lineup included newcomers BILL GARDNER, a tackle and end from Carlisle Indian School, Hube Wagner, an All-America end from Pittsburgh, and EARLE (GREASY) NEALE, the coach at West Virginia Wesleyan and an outstanding halfback.

Massillon also had some big names in its lineup. The Tigers were represented by four former Notre Dame players – ends Knute Rockne and Sam Finegan, tackle Keith Jones, and halfback Gus Dorais – and Ohio State halfback Maurice Briggs.

As the two games between the renewed rivals approached, it was just like old times, with Canton and Massillon appearing to be the best teams in the state. Each had lost only once, and Canton’s defeat had been while traveling out of state, a 9-3 verdict to the Detroit Heralds. With fans anxiously awaiting the first game, Cusack, in a move reminiscent of the old Canton-Massillon wars, signed the best football player in the world – JIM THORPE.

Thorpe first earned national attention in 1911-12, when he was an All-America halfback at the Carlisle Indian School. He received the acclaim of the world when he won gold medals in both the decathlon and the pentathlon at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm. It was there that King Gustav V of Sweden told him, “Sir, you are the greatest athlete in the world.”

Thorpe also had played pro baseball, as well as football, with the Pine Village team in Indiana. When Cusack contacted him, Thorpe had slid into semi-oblivion and was coaching backs at the University of Indiana. Nevertheless, he was still Jim Thorpe. The great Indian was a star at any sport he set his mind to, but on a football field he was in a class by himself.

Some players could run as well, some could pass, a few were on a par defensively, and a very few could kick equally well, but no one at the time – or possibly since – combined all these skills to an equal degree of perfection. Still, when fans heard that Thorpe had been promised $250 for each game, they figured Cusack had lost his mind.

But Cusack had the last laugh. The paid attendance for the Bulldogs’ games had averaged 1,200 before he signed Thorpe. For the final two games with Massillon, Thorpe helped draw crowds of 6,000 (where Massillon raised their ticket prices to seventy-five cents) and 8,000. Everyone wanted to see the world’s best football player in action.

Unfortunately, Thorpe didn’t help the Bulldogs as much on the field as off in the first game as Massillon won 16-0. Thorpe didn’t start, although he did break loose for a 40-yard run to the Massillon 8-yard line, before he slipped trying to avoid Dorais.

Canton vs Massillon, 1915

“Nowhere in this country today are there two football teams possessing such a galaxy of stars as do the Tigers and Bulldogs.”

Massillon Independent, November 14, 1915

“There was a large amount of money [bet] up on the game and the fans, crowded into a stadium much too small for the crowd, were at a fever pitch when the game started.”

Canton Daily News, November 29, 1915

Two weeks later, the teams met at Canton, with the Bulldogs winning 6-0. First, Thorpe dropkicked a field goal from the 18-yard line and later he made a 45-yard field goal from placement. But it was one of the most exciting finishes ever that earned the game its place in history.

The second game was played before a crowd so large that fans had to stand in the end zones. Ground rules for the game were adopted providing that any player crossing the goal line into the crowd had to be in possession of the ball when he emerged from the crowd. Late in the game, Massillon drove the length of the field to try to score the winning touchdown. That is when the fireworks really exploded, according to Cusack:

Maurice Briggs, right end for Massillon, caught a forward pass on our 15-yard line and raced across our goal right into the midst of the “Standing Room Only” customers. Briggs fumbled – or at least he was said to have fumbled – and the ball popped out of the crowd right into the hands of Charlie Smith, the Canton substitute who had been following in hot pursuit.

Referee Connors, mindful of the ground rules made before the game, ruled the play a touchback, but Briggs had something to say about that. “I didn’t fumble!” protested the Massillon end. “That ball was kicked out of my hands by a policeman – a uniformed policeman!”

That was ridiculous on the face of it. Briggs was either lying or seeing things that didn’t happen to be there — for most everybody knew that Canton had no uniformed policemen in those days. But Briggs was unable to accept this solid fact.” It was a policeman!” he insisted. “I saw the brass buttons on his coat.”

As the arguing over the call continued, the crowd grew more and more restive. Only three minutes remained in the game that would determine the Ohio professional championship. If the touchdown counted and Massillon either won with an extra point or tied, the Tigers would win the undisputed championship. However, if the score did not count and the Bulldogs held on to win, they might be awarded the title. Finally fans of both teams could stand the strain no longer, broke down the fences surrounding the field, and swarmed by the thousands onto the playing surface.

The officials, unable to clear the field, ended the game. However, the officials were not allowed to escape. The Massillon team and its fans demanded that they settle the matter by making a definitive statement about the referee’s decision. The officials agreed to make the statement, but only if it were to be opened and read by the manager of the Courtland Hotel at 30 minutes after midnight. That would give the officials time to leave town, thereby avoiding the wrath of either the Canton or Massillon fans.

That night the lobby of the Courtland was filled to capacity with both Canton and Massillon fans, waiting for the statement to be read. When it was announced, the fans learned that the officials had backed the referee’s decision and ruled that the Bulldogs had won the game. The last chapter of the season did not end at the hotel, however. It was not until 10 years later that Cusack solved the mystery of Briggs’s fumble and the phantom policeman. As Cusack recalled:

While on a visit back to Canton I had occasion to ride a street car, on which I was greeted by an old friend, the brass-buttoned conductor. We began reminiscing about the old football days, and the conductor told me what had happened during that crucial final-quarter play back in 1915. Briggs, when he plunged across the goal line into the end zone spectators, fell at the feet of the conductor, who promptly kicked the ball from Briggs’ hands into the arms of Canton’s Charlie Smith.

“Why on earth did you do a thing like that?” I asked.

“Well,” he said, “it was like this – I had thirty dollars bet on that game and, at my salary, I couldn’t afford to lose that much money.

That kick might have saved the conductor $30, but it cost Massillon a consensus state championship. Instead, the Ohio League title race was left in a muddle, with three teams – Canton, Massillon, and Youngstown – all claiming the championship. As it turned out, the only clear winner in 1915 was Canton, and that was off the field, where the signing of Thorpe not only led to immediate financial success but gave the Bulldogs a bright future.

Thorpe actually did more than that, helping football throughout Ohio. More important than anything he did in any single game, Thorpe’s presence at Canton focused the attention of the whole country on Ohio professional football. More players of quality began arriving and both attendance and salaries went up. Ohio sportswriters – without blushing – began to trumpet the “world professional championship.” True, pro and semi-pro teams could be found from New England to Iowa in nearly every town will eleven able-bodied men and a flat expanse of 100 yards, but they all took the aspect of minor leaguers; Ohio held the majors.

The presence of Thorpe on the field in football-crazy northeast Ohio doubled the attendance and escalated the demand for former college all-stars to the point where no team could hope to become a state, regional or national championship contender without a significant number of paid former college stars on its team. Soon, the annual talk of forming a real pro league – with Thorpe’s Canton Bulldogs as the cornerstone – became more vocal than ever before.

Golden Era of Canton Bulldogs Football

The following year the Bulldogs, with Jim Thorpe, beat Massillon 24-0, and went unbeaten at 9-0-1. They were regarding as the best team in the Ohio League as well as the entire country, outscoring their opponents 257 to 7 and giving up only one touchdown all season.

In consecutive weeks they showed the country how good they were by blowing out the Buffalo All-Stars, 77-0, then the following week crushing the New York All-Stars, 67-0.

Because Thorpe was able to draw big crowds, Cusack was able to put together a financially stable squad that included several All-Americans. The average attendance prior to Thorpe’s arrival was around 1,500. That soon rose to 5,000, 6,000 and eventually 8,000 spectators, which was the capacity of Canton’s Lakeside Park.

For the two big games at the end of the year against cross-town rival Massillon, each game drew over 10,000 fans- some reports claim that the game in Massillon had nearly 15,000 spectators.

Massillon vs Canton, 1916

It was a gala day in Massillon. Thousands of Canton fans were bedecked with red and white. They had a forty-piece band backing them up on the east side of the gridiron. Massillon fans were dressed in orange and black, and they too had a band. Unfortunately, there was a strong there was a strong wind, the field was soft, and the footing was unsure. The rough-and-tough game ended in a 0-0 tie.

The second game…Massillon was outplayed and outclassed. Jim Thorpe and company gave an artistic exhibition of all that is great in the rough sport, through laboring under trying conditions. A muddy field proved a woeful handicap, robbing the contest of many of the anticipated features…Jim Thorpe was a veritable demon and Pete Calac was extraordinary…This was a regular victory. It had no semblance of a fluke. If left no room for alibis.

Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 3, 1916

Thorpe would remain pro football’s chief attraction until Red Grange entered the pro game in 1925.

In 1917 the Bulldogs once again claimed the Ohio League championship by finishing with a 9-1 record. Neither Canton nor Massillon played during the 1918 season because of World War I and the flu epidemic. During that missed season Jack Cusack wanted a bigger pay day. He decided to try and strike it rich by leaving Canton to start up an oil business in Oklahoma. He sold the Bulldogs to RALPH HAY, a successful automobile dealer in Canton.

In 1919 the first rumblings of a “pro league” was being discussed by the football press and team managers. Ralph Hay knew his Bulldogs would be at the fore-front of this movement. In Canton, Hay responded cautiously, insisting, “We will be on the ground floor when a meeting for the formation of a league is called.”

But, he added, the Bulldogs wouldn’t even consider such thoughts until the present season ended. Hay was no doubt miffed that rank newcomers to the pro football wars had initiated the call for a league without checking with Canton. Additionally, he had more immediate worries. Canton’s first meeting with Massillon was scheduled for the following Saturday.

On November 16, Canton staked its claim for the Ohio League championship with a 23-0 victory over Massillon. Thorpe again played magnificently, but he was helped by two other Indians, Pete Calac and Joe Guyon, the latter having signed with the Bulldogs out of Georgia Tech. Almost certainly, he gave Canton the best set of backs in football – pro or college.

In the next three weeks, all the pretenders to the Bulldogs’ throne were eliminated. Massillon defeated Cleveland 7-0, while Canton ended any title hopes in Akron by beating the Indians 14-0. On Thanksgiving before a crowd of 10,000 in Cubs Park at Chicago, the Bulldogs met Hammond (IN).

At this time the Indiana team had added a high-priced player, former Northwestern star John (Paddy) Driscoll, one of the best kickers and open-field runners in the game. Nevertheless, Thorpe’s eight-yard touchdown run and a stingy Canton defense gave the Bulldogs a 7-0 victory.

Three days later, the Bulldogs met the Tigers again, with the Massillon players and fans hoping a victory in the season finale could propel them to the national title.

But Thorpe took over. In the third quarter he kicked a 40-yard field goal for the only points of the game, and in the fourth quarter he punted 95 yards to keep the Tigers away from Canton’s end zone. The Bulldogs left the field with a 3-0 victory, a 9-0-1 record, and the state and national professional championships.

NFL's First Meeting (September 17,1920)

On a hot and muggy Friday night in Canton, Ohio on September 17th ten professional football teams convened at the automobile showroom of Ralph Hay. The football managers arrived into town by train but nobody really stopped the presses to announce their arrival.

Hay really didn’t know how many owners would actually show so his small office wasn’t big enough to have the meeting so they moved out in the spacious showroom with the cars on display. It was quite a scene as these milestone men met in the showroom of an automobile dealer. One of the ten owners would always remember the trip to Canton. George Halas in his autobiography, Halas, described the experience:

Morgan O’Brien, a Staley engineer and a football fan who was being very helpful in administrative matters, and I went to Canton on the train. The showroom, big enough for four cars -Hupmobiles and Jordans – occupied the ground floor of the three-story brick Odd Fellows building. Chairs were few. I sat on a running board.

At the meeting were the four teams who were at the August get-together with the same representatives; Hay and Thorpe for Canton; Neid and Ranney for Akron; O’Donnell and Cofall for Cleveland; and Storck for Dayton. Also present were Walter H. Flanigan, the veteran manager of the Rock Island (IL) Independents; Earl Ball of the Ball Mason Jar Company and the backer for the Muncie (IN) Flyers; George Halas and Morgan O’Brien, representing A.E. Staley’s Decatur team; Chicago contractor Chris O’Brien, who operated the Chicago Cardinals; Leo Lyons, represented his Rochester (NY) Jefferson and Dr. Alva A. Young, owner of the Hammond (IN) Pros.

After some informal discussion beforehand the meeting started at 8:15 pm by Hay. Frank Neid of the Akron squad took the minutes and had them typed up on letter head of the “Akron Professional Football Team.”

Although the meeting officially started at 8:15 some of the main issues might’ve been decided before Hay suggested they go on the record. What they did decide was to change the name of the organization to the American Professional Football Association (APFA). The managers might’ve felt that the use of the word “association” was much more loose and general than using a word such as “league,” denoting maybe less of a commitment.

Several managers urged Hay to take the association’s presidency but he realized that the organization needed a bigger name to earn respect from the public and the nation’s sports pages. “Thorpe should be our man. He’s by far the biggest name we have. No one knows me,” Hay would say. So they choose the biggest name in pro football to be President – Jim Thorpe.

Old Jim was elected and sure enough Hay was right as the headlines in sports pages across the country would lead with the naming of Thorpe as the league’s President. Most of the managers in the room knew that Thorpe’s executive abilities didn’t match his athletic prowess but they expected Hay to work behind the scene to help guide the league. Stanley Cofall was named Vice-President and Art Ranney was elected secretary-treasurer giving the three main Ohio clubs all the executive positions.

The group decided to charge $100 fee for membership but this was just for show. “We announced that membership in the league would cost $100 per team. I can testify no money changed hands. I doubt if there was a hundred bucks in the whole room. We just wanted to give our new organization a façade of financial stability,” Halas would admit. Other business discussed was the appointment of a committee to draw up rules and regulations and the decision to furnish a list of all players used during the season to all clubs by the first day of the new year.

Accorded to the league minutes the three major problems in professional football had not been directly addressed. But the association must’ve talked about them because the media coverage of the meeting would stress the action of the managers not mentioned in the minutes. Most of the newspapers announced that the Association would not use undergraduates and that all contracts would be honored. News of the new pro football league spread across the country but it was not the main headline in every sports page.

Even in the Canton Repository the day’s big news was the Canton Bulldogs’ signing of Pete “Fats” Henry, the former Washington & Jefferson All-American tackle and only on the following page did the paper mention that a new pro football league was formed.

APFA Seasons (1920-1921)

In 1920 the APFA (forerunner of NFL) saw the Akron Pros win the first ever championship for the new league. The Canton Bulldogs, under Hay and coach Thorpe, started strong with a record of 6-1-1, but faded by winning only one of its last five games to finish 7-4-2 (a 8th place finish). After the season Thorpe left the Bulldogs and joined the Cleveland Indians.

Cap Edwards took over as coach, but the Bulldogs came up short again finishing with a 5-2-3 1921 record and a 4th place finish in the APFA.

NFL Champs!!! (1922)

As the league owners’ changed the name from the APFA to the National Football League (NFL), veteran owner Ralph Hay and new coach GUY CHAMBERLIN, the Canton Bulldogs unloaded most of the mediocre squad from 1921 and rebuilt in 1922.

Chamberlin began with one marvelous player already on the roster, roly-poly WILBUR “PETE” HENRY – nicknamed “Fats.” At 5-11 and 245 pounds, Henry looked like an amiable pudding until the ball was snapped. Then his surprising speed, agility and strength made him by nearly all accounts the best tackle of the day.

A bulldozing blocker and bone-crushing tackler, he could slip into the backfield to become an occasional powerhouse line-smasher or zip downfield as a surprise receiver on tackle-eligible plays. On top of all that, he was an outstanding punter and deadly drop-kicker.

To man the opposite tackle, Chamberlin added fellow University of Nebraska alumnus ROY “LINK” LYMAN, another who was to enjoy a long and storied NFL career. Lyman was a “finesse” player, generally credited with pioneering defensive tackle play along more sophisticated lines with his shifting, sliding style. Both Lyman and Henry are enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Former Chicago Staley TARZAN TAYLOR and second year pro BOB “DUKE” OSBORN gave the Bulldogs a brace of strong guards. Osborn added a colorful touch in that he usually wore a baseball cap instead of a helmet. Two players split time at center: rookie Bill Murrah from Texas A&M and ageless Norman “Dutch” Speck, nearing 40 but still capable.

At one end, Elmer “Bird” Carroll was rated by his coach as one of the best. Chamberlin should have known – he was THE best! No doubt Coach Chamberlin’s most valuable player was himself. On offense, he could block with anyone and showed a knack for catching key passes. On defense, he was unmatched at his position.

More than anything, he could inspire his team. In 1922 he began a streak that marks him as the most successful player-coach in NFL history – four championships in five years and a career winning percentage of .780.

The Canton backfield, however, looked weak at the start of the season. After experimenting with a few combinations, including himself at wingback, Chamberlin settled upon rookie Walcott “Wooky” Roberts from Navy as his blocking back, converted tackle Ed Shaw into a fullback, and used second-year man Harry Robb at wingback and journeyman Norb Sacksteder at tailback.

Later in the season, the Bulldogs added backfield strength in veterans Cecil “Tex” Grigg and Lou “The Hammer” Smyth and rookie Wallace “Doc” Elliott. This essentially undistinguished group of backs combined with the strong line to form a granite-hard defense and a steady ground-oriented attack.

The Bulldogs dominated the NFL in 1922. Holding off the Chicago Bears (9-3 record) and the Chicago Cardinals (8-3), Chamberlin’s squad went unbeaten with a record of 10-0-2. They outscored their opponents 184-15.

The National Football League gave out no awards in 1922 except for the tiny gold football watch fobs the members of the champion Canton Bulldogs received after the season. If the struggling league wasn’t going to invest in trophies for individuals, it was certain that the wire services who gave the NFL scant coverage weren’t about to crown a Player of the Year as they now do.

If they had, they might have given the nod to Paddy Driscoll, the Chicago Cardinals’ great triple-threat. Other likely candidates might have been Racine’s Hank Gillo, who scored the most points, or player-coach Guy Chamberlin, the Canton leader.

But of all the achievements of 1922, the one that boggles the mind is Canton’s record of allowing only 15 points in a dozen games. And although that was obviously the result of a team effort, one man stood above the other Canton defenders in both reputation and performance. If anyone had seriously considered naming a Player of the Year, he couldn’t have done much better than to choose Pete Henry, Canton’s magnificent tackle.

With the league’s strongest lineup, Canton couldn’t have kept its payroll below $1,200 per game by any stretch of the imagination. Whether Hay planned to sacrifice his own money for the honor of his city or really expected to pay the bills out of the gate receipts, the simple fact was the Bulldogs were winners on the field and losers in the ledger.

Despite near-filled stands at Canton’s Lakeside Park, the small capacity meant the ‘Dogs usually made more money – though not enough – by playing on the road.

Ralph Hay Steps Away From Football

As summer arrived the situation in Canton took an unexpected turn. Ralph Hay, who owned the Canton Bulldogs since 1919, wanted out of the football business. His asking price was $1,500, which, after a great deal of hand-wringing with Canton businessman, was about $500 more than they thought the 1922 champions were worth.

Things were still up in the air when Hay and Chamberlin left for Chicago in July to attend the annual summer meeting. At the meeting Hay assured Carr, other owners and the city of Canton that the Bulldogs would play in 1923. Chamberlin would continue as coach-player. He just needed to close the deal back home.

When Hay returned to Canton he unloaded the Bulldogs onto a group of local businessman, who formed the CANTON ATHLETIC COMPANY. The Canton A.C listed 18 stockholders, including H.H. Timken (Owner of Timken Bearing), Guy C. Hiner (Canton Bridge Company) and Ed E. Bender (owner of Bender’s restaurant – NFL President Joe Carr’s favorite Canton nightspot). Chamberlin’s coaching assured the team’s success on the field but didn’t off it.

In his four years as owner he brought two national titles (1919, 1922) to Canton, helped start what was now known as the NFL, gained a lot of publicity for his Hupmobile business and lost a ton of money. Although four years doesn’t sound like a long time, Ralph Hay, just like his predecessor with the Bulldogs – Jack Cusack – was another vital contributor to the growth of the pro football.

Running a Pro Football Team

Running a pro football team at that time did have its problems. It cost us $3,300 to put a team on the field for a game. When we played on the road, we got a guarantee of $4,000 a game. That was to cover the players, player salaries and the expense of traveling. In those days, of course, there were no airplanes; we traveled by train in sleepers. When we’d leave, say for Chicago, we’d occupy the whole sleeper. We had 18 men and the trainer and we’d take this sleeper out of Canton on Friday night to Chicago, stay the one night, play on Sunday, and come back. It was tough.

Lester Higgins, treasurer, Canton Bulldogs

Back-to-Back Champs (1923)