Some might describe it as a betrayal…

Others might simply consider it as a wonderful business opportunity…

In reality, it prompted a rash of hard feelings that eventually shattered the trusted business partnership between two legendary NFL pioneers.

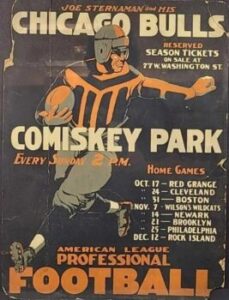

In this episode of “When Football Was Football,” we’ll look closely at the arrival of the original Chicago Bulls back in 1926. Unlike the NBA champions of almost 70 years later, these Bulls were formed to participate as members of the newly formed American Football League. And the creation of that team sent shockwaves through the existing pro football establishment in Chicago.

Our story actually begins a year earlier, in 1925, when the legendary Red Grange, the All-American halfback from the University of Illinois, joined the Chicago Bears immediately after his final collegiate game against Ohio State on November 21, 1925.

The fact that Grange signed with a professional football team was not entirely unexpected. What was a bit shocking was the fact that George Halas, owner of the Bears, signed Grange right after his last college game, rather than following his graduation.

This appeared to contradict one of the precepts of the early NFL: that it would not dip into the collegiate ranks for players. But it was George Halas who interpreted the rule a bit differently, and in doing so incurred the wrath of prominent members of the college football fraternity. Halas figured that since a college player had completed his eligibility, he was then immediately “eligible” for professional competition.

Grange Tours Attract Large Crowds

Still, the NFL did not seem concerned with the Bears’ contract with the ultra-popular Grange midway through the academic year, especially with the enormous visibility for the league generated by the Bears and Grange when the club departed on a pair of tours devised to take advantage of the player’s nation-wide reputation.

In those chaotic early days of the NFL, crowds were not competitive with those attracted by college football or major league baseball. But the arrival of Grange changed all of that with the Bears playing before a crowd of 70,000 in New York just a few weeks after entertaining less than 2,000 in a home game with Hammond.

Pyle Demands Piece of Bears

Following the completion of those two tours, Grange and his manager—the unique and ambitious C.C. Pyle–presented Halas with a bewildering offer that would allow Grange to play for the Bears in 1926. In this scenario, Grange would remain in the Bears’ fold, said Pyle, if he and Grange would be awarded a one-third share of the ownership of the Chicago Bears.

Halas was flabbergasted by this suggestion and ultimately refused the offer, even though he would be relinquishing the biggest box office draw in the history of the early NFL. He said: “One-third ownership? An equal partnership with Dutch Sternaman and me? No, no, no! A percentage of earnings, yes, that was negotiable, but a share of ownership, no!”

After being rebuffed in their bid to secure part ownership of the Bears, Pyle and Grange then marched into the winter meeting of the NFL in early 1926 and requested an NFL franchise of their own, specifically in New York.

Pyle was so confident that his request would be accepted that he signed a five-year lease on Yankee Stadium where his team would play its home games. But the brethren of New York Giants’ owner Tim Mara never blinked and the NFL refused Pyle’s request, seemingly washing its hands of the belligerent deal-maker.

Chicago Bulls Arrive

So, with a well-known field but no team or league, Pyle convinced Grange to join him in establishing and supporting the new American Football League (AFL), a direct competitor of the National Football League. Nine teams were part of the AFL, including the New York Yankees which would be fronted by the popular Grange. In Chicago, both the Bears and the Cardinals were threatened by the presence of the freshly minted Chicago Bulls of the AFL.

The Bulls then dented the armor of the Cardinals by quickly renting Comiskey Park, the recent home of the Cardinals, thus forcing the club to host its home games back in tiny Normal Park, the original home field of the team when it entered the national professional ranks in 1920.

For the Bears, the appearance of the Chicago Bulls posed a more subtle, yet personal, issue for George Halas. Pyle and Grange attracted Joey Sternaman of the Bears to serve as the key performer and the president of the Bulls. This offer included a share of the ownership in the Chicago Bulls.

Joey Sternaman, of course, was the brother of Dutch Sternaman, the partner of Halas and co-owner of the organization. It should be noted that Joey Sternaman also owned shares of the Chicago Bears which caused some concern for Halas when Joey announced that he would be moving over to the Bulls in 1926. Joey resigned his position on the Bears’ Board of Directors on May 14, 1926, which would appear to minimize any personal conflict of interest between the Bears and the Bulls.

Question of Loyalty

Yet, how would it affect Dutch Sternaman? Would he be able to manage his own loyalty to the Bears while still maintaining loyalty to his brother Joey? Halas was likely miffed that Joey Sternaman essentially betrayed him and loudly added another competitor to the now crowded battle for pro football tickets in a town that already hosted both the Bears and the Cardinals.

It would be difficult to fault Joey for accepting the opportunity to not only star for a professional football team but to also be its owner as well.

And, after noting his own financial success with Red Grange the previous season, Halas certainly must have feared that the lurking presence of Grange as a rival could easily impact not only his attendance but also the very existence of the NFL. If Grange, Pyle, and their eager new league could be successful, would it drop the NFL to its knees or obliterate it completely?

Behind the scenes, the arrival of Joey Sternaman and the Bulls quietly contributed to the beginning of a gradual split between Dutch Sternaman and George Halas. Halas first noticed it when the time arrived for NFL teams to plot out their schedules for the upcoming year. Unlike today, the creation of NFL schedules was rather haphazard and often adjusted during the season.

When the teams gathered at the NFL meeting in Philadelphia in July of 1926 to address the upcoming league schedule, the co-owners of the Bears promptly presented their own separate plans for the Bears’ 1926 schedule. Obviously, this was quite confusing to the other owners and NFL President Joe Carr asked the owners to decide on which representative of the Bears should be the designated “voice” in the schedule-making.

Bears' Owners Disagree

The other owners sided with Halas, who was primarily perturbed about the disagreement between Dutch and himself over the date of October 17, 1926. Halas insisted on playing the Cardinals on that day while Dutch preferred to meet their oldest rivals on Thanksgiving Day instead. The games with the Cardinals were always a handsome payday for both teams in Chicago, so Halas was bewildered by the scheduling proposed by Dutch as Halas later explained in his autobiography:

“On my schedule, I had penciled in for that day (October 17) a game with our old rivals, the Cardinals, a match that usually produced the biggest gate of the season. Dutch wanted to play the Cardinals on Thanksgiving Day. When other league members learned that October 17 was the day Joey Sternaman had scheduled a game in Chicago between his new club and the New York Yankees starring the great Red Grange, the reason for differences between Dutch and me became obvious.

A double bill in Chicago on the day I proposed would hurt the Bulls; keeping the Cardinals game on Thanksgiving Day would help them. The situation caused me heartache. Dutch, Joey, and I had gone through hard times together. Now, when prosperity was here, we were divided. I was finding adversity more pleasant than prosperity.”

Bulls Outdraw The Bears!

Ultimately, the Bears and Cardinals game was played on October 17 and attracted a crowd of 12,000. However, the Chicago Bulls hosted Red Grange and the Yankees on that same day and drew 17,000 people. Would the AFL be able to maintain this surprising attendance? Could this new circuit doom the NFL?

Unfortunately, unless the star power of Red Grange was making an appearance, attendance at other AFL games, including those in Chicago, was meager. Only four teams remained in the AFL by early November of 1926, and the league itself failed to return in 1927.

Eventually, Joey Sternaman returned to the Bears, as did Red Grange, but the partnership between Halas and Dutch Sternaman was shaky. The pair decided to relinquish their co-coaching duties in 1930 and Halas finally bought out Sternaman in 1932.

Today, when we hear the name of the Chicago Bulls, we quickly remember the magical era of Michael Jordan and the six NBA championships the Bulls collected.

Few, if any, have any knowledge of the original Chicago Bulls—the child of an ambitious gridiron family known as the American Football League which has largely been forgotten. But for that one shining moment in 1926, the Chicago Bulls certainly caused some concern for the rival National Football League!

Author and Host - Joe Ziemba

Joe Ziemba is the host of this show, and he is an author of early football history in the city of Chicago. Here, you can learn more about Joe and When Football Was Football, including all of the episodes of the podcast.

Please Note – As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases

Resources

More From When Football Was Football

Paddy Driscoll’s Almost Perfect Season

Back at the beginning of the National Football League in...

Read More120,000 Fans Witness High School Football Game in 1937!!!

Let’s set the stage… It was a warm November afternoon...

Read MoreIn The Beginning: An Interview With Joseph T. Sternaman

And, you may ask, who is Joseph T. Sternaman? Sternaman...

Read More1948: The Last Hurrah of the Chicago Cardinals

Cardinals’ fans are familiar with the long, sad story concerning...

Read More