Throughout the history of professional football, every so often you might notice a club roster that is so strong, so impressive, and so very talented, that you just could not anticipate anything less than total success for that specific team.

1931 CHICAGO BEARS

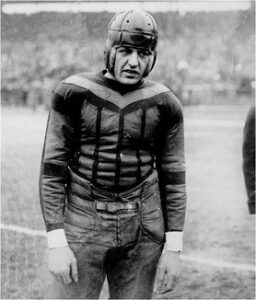

This may have been the case with the 1931 Chicago Bears, a squad that featured no less than four future Hall of Famers in Red Grange, Bronko Nagurski, Link Lyman, and George Trafton. Despite this wealth of talent, the Bears stumbled to a good, but not great, 8-5 record, finishing in just third place in the final standings of the National Football League.

This was before the league was divided into two divisions and there was no playoff system in effect, so that last game was indeed the end of the season. While specific reasons for a team’s failure to achieve expectations are difficult to identify, opponents of the professional game at the time in 1931 might eagerly point out that the pros—unlike their collegiate counterparts—simply didn’t care about anything more than a pay day.

Were the Bears doomed to failure because of the players’ lack of “spirit or zest” for the game itself? Was their roster loaded with highly paid individuals who simply did not care? Were they unprepared, indifferent, or selfishly inspired or uninspired compared to the “rah-rah” atmosphere at the collegiate level?

In reality, this type of theory was closer to gossip than anything else. There was certainly a veil of unintended secrecy surrounding the workings of professional football teams at the time. Without social media, television, or other current communication modes available in 1931, there wasn’t much information from newspapers featuring behind-the-scenes access about players or teams.

While newspapers covering collegiate teams might provide extensive by-lined game previews and post-game coverage, there was little by comparison on the professionals in terms of creative or unusual feature articles. Readers seeking insightful “inside” information on their favorite team would often need to rely on redundant wire service coverage.

Supporters of the college game pointed to the ever-present “zest” of the game as being far superior to the professionals. But does “zest” ensure a better product on the field? In terms of the times, perhaps we can agree that “zest” on the university level was marked by the enthusiasm and loyalty of the players and their determination to win at all costs for the honor and glory of their academic institution.

On the other hand, did the pros really possess any “zest,” and if so, what prompted this attribute? It was, in all likelihood, a paycheck. Or was there something more?

ZEST OF PRO FOOTBALL PLAYERS

And so, this brings us back to the 1931 Bears, a club that despite its talented roster, moved into mid-season with a lackluster 3-3 record. Could this truly be blamed on a lack of spirit or “zest” from the professionals?

“Zest” is a challenging word to define, especially in terms of professional football, but with the Bears ailing a bit on the field, the Chicago American newspaper received permission from the organization to investigate the possibility that perhaps the pros did lack that type of spirit that propelled the collegians in their on-field performance. As a result, the Chicago American provided us with a rare peek behind the scenes with a light-hearted look at the “zest” of professional football players.

Of course, we must remember that the professional football scene in 1931 was far different than it is today where it reigns as the most beloved of all professional sports in this country. We were still three years away from the first College All-Star game in 1934 and five years from the inauguration of the initial NFL draft in 1936. Fans loved debating the respective merits of both sides of the football spectrum, citing whether the pros or the collegians played the better brand of football.

The college game continued to flourish with massive crowds pouring into campus stadiums on bright autumn afternoons. The pros, meanwhile, continued to struggle with attendance issues despite the sudden ascension of the game during the debut of the two Red Grange tours in 1925 and 1926.

And so, the article by Jim Gallagher in the Chicago American attempted to cover the chasm in the 1931 pro ranks between that elusive “zest” and the disengaged pro football worker, who apparently was only in it for the money.

The results were a bit surprising based on rare locker room interaction conducted by the reporter since interviews with players were not always documented on a regular basis in the media in those early days of the NFL.

OFTEN THRILLING AND ALWAYS DOGGED!

The article appeared on Thursday, November 5, 1931 when the talented Bears were embroiled in a busy schedule and preparing for a Sunday match-up with the invading Portsmouth Spartans at Wrigley Field in Chicago. Following a tough 6-2 defeat at the hands of the Green Bay Packers the previous weekend on November 1, the Bears had slipped to that 3-3 mark midway through the season but hoped to salvage their title hopes by succeeding in the next five games over the upcoming 21 days in November, beginning with the Spartans.

The loss to the Packers was especially tough since the defeat left the Bears well behind 8-0 Green Bay in the NFL championship race. The Green Bay Press-Gazette described the action thusly: “The game was tense, occasionally sensational, often thrilling and always dogged.” Yet the Bears could only manage a safety for their sole points of the day.

Meanwhile, the Packers’ offense struggled as well, with the team’s lone touchdown occurring when Mike Michalske rambled 80 yards with an intercepted pass thanks to massive Packer’s lineman Cal Hubbard destroying quarterback Carl Brumbaugh as he attempted a pass, according to the Press-Gazette: “Brumbaugh slipped back to pass. Big, broad Cal Hubbard came charging in at him like a locomotive.

Brumbaugh couldn’t throw the ball to the man the play called for as Cal smashed into him, so he threw wildly…Mike Michalske came bounding out from behind the line. He grabbed the ball on his own 20-yard line and started to gallop.”

EVERY MAN WOULD PLAY FOR NOTHING

Three days later, Jim Gallagher showed up in the Bears’ locker room to conduct interviews for his article which was intended to focus on the lack of “zest” among professional football players. Much to his surprise, he quickly discovered just the opposite! Instead of grumpy, uncooperative players, Gallagher encountered a room full of dedicated, but playful, individuals who were still recovering from the tough loss to Green Bay.

Gallagher described his 8:30 am arrival time at Wrigley Field to be “unearthly,” yet he found the Bears’ players to be prompt and anxious for practice to begin. He asked Garland Grange (brother of Red Grange) why he showed up so early for the 9:30 practice. Grange replied: “Oh, I just like to be here in plenty of time.”

Gallagher then brought up that delicate question about whether the money-hungry pros would ever agree to play, let alone have a chance, against the top amateur collegians. Grange was quick to respond: “Gosh, if we could only get Northwestern or Notre Dame for a charity game. Every man on this club would play for nothing—just for the pleasure of beating them!”

Adjacent to Garland Grange, coach Ralph Jones of the Bears was quietly diagramming a play on the blackboard for linemen Lloyd Burdick and Bert Pearson. Naturally, Gallagher asked Grange what type of play they were reviewing. Grange replied: “They’re going over that play that lost the Green Bay game when Hubbard came through and deflected Brumbaugh’s pass to Michalske when he ran eighty yards for their touchdown.”

Gallagher was a bit shocked by that answer and said to Grange: “Why, I thought you only played for the dough. And you tell me they’re still worrying over a play in a game here days ago?”

Indeed, the members of the Bears were not only worrying about that specific play—they were still fuming about it, forcing Gallagher to note to his readers: “It seems I was wrong. They’ll worry about that lost game until they beat the Packers—the ‘lucky stiffs!’”

RED GRANGE WITH TWO FRONT TEETH MISSING

The great Red Grange strolled into the locker room ready for practice with a swollen upper lip and a pair of front teeth missing after the Green Bay battle, while a prone halfback named Joe Lintzenich with serious leg and wrist injuries was being worked on by trainer Andy Lotshaw. Despite his injuries, Lintzenich told Coach Jones: “Oh, the leg and arm hurt, and I can’t throw passes—but I’ll be able to get into practice today.”

Again, this was not what reporter Gallagher had expected to witness; he anticipated that a wounded pro warrior would milk his injury as long as possible in order to preserve his health for future paychecks. But here was Lintzenich, who could barely walk, intending to practice with the rest of the Bears on a cold November morning.

As the full roster of players swarmed into the locker room, Gallagher was surprised once more when the expected group of dour silent men complaining both about the early hour as well as the need for practice failed to materialize. Instead, he wrote: “By 9 o’clock the room had filled with players. Early morning isn’t generally a cheerful time, but there was the same horsing around and kidding that you find in any dressing room.”

Coach Ralph Jones, who took over the team following the 1929 season when co-owners Dutch Sternaman and George Halas “retired” from coaching, acknowledged the positive personality of the club as reported by Gallagher: “Coach Jones declares that never, in high school or college, has he worked with a more amenable group of men, with any gang more willing and able to learn—or which enjoyed playing any more.”

IT’S STILL A LOT OF FUN, JIMMIE!

Gallagher then moved outside at Wrigley Field as Jones moved the team through a lengthy, nearly three-hour practice session focusing on a “dummy” scrimmage that Gallagher painted as “No fun, no tackling, no contest, just running through plays for a couple of hours. Of all tiresome, uninteresting proceedings, dummy scrimmages is it.”

In a sense, Gallagher was amazed by the lively interaction he observed during the practice drills, along with the readily apparent enthusiasm of the veteran players. He added: “Two hours after they started, they were still sweeping though plays with speed, precision and vim.

They were enjoying it –and none more than [quarterback} Laurie Walquist and [center] George Trafton, who should be fed up with football if any one should, after all their years in the game. In the dressing room later, Laurie called over [to Gallagher] as he strolled out of the shower room: ‘It’s still a lot of fun, Jimmie.’ And by gum, I believe it was!”

Perhaps they were revitalized by the positive spin of Gallagher’s article, but the Bears then rattled off four straight wins beginning with the Portsmouth game to launch back into title contention with a 7-3 record. However, no one was going to catch the Packers that season as Green Bay snatched the NFL crown with an impressive 12-2 ledger. The Bears finished with the aforementioned 8-5 mark and third place, a step ahead of the 5-4 Chicago Cardinals back in an era when all NFL teams did not play an equitable schedule.

But the Bears were not to be denied, winning NFL championships in both 1932 and 1933. If James Gallagher’s article proved anything, it was that professionals could still enjoy the various aspects of the game in much the same way that collegiate players did—or so we thought.

In a concluding statement to his article where he provided a final thought regarding his quest to discover if there was any “zest,” in the NFL, Gallagher recalled a recent experience with a college locker room: “I thought, too, of some scenes in college dressing rooms, where one man charged that a teammate had deliberately shirked on a play, because he didn’t like the ball carrier; where the coach was called a dummy by his high-priced stars—and high-priced is the right word; where one clique hardly spoke to another because of jealousy.

Just what is this ‘zest’ for the game? Could it be that the wicked pros really have it, after all?”

Author and Host - Joe Ziemba

Joe Ziemba is the host of this show, and he is an author of early football history in the city of Chicago. Here, you can learn more about Joe and When Football Was Football, including all of the episodes of the podcast.

Joe Ziemba Books

Please Note – As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases

Resources

More From When Football Was Football

Big Jim Thorpe’s Forgotten Football Vacation

It was December of 1924 when Big Jim Thorpe of...

Read MoreSearching for the “Zest” of the 1931 Chicago Bears

Throughout the history of professional football, every so often you...

Read MoreUgly Passers, Brick Walls, and Feisty Cardinals

Since the Arizona Cardinals are the NFL’s oldest team, with...

Read MoreThe NFL’s Forgotten Gold Medalist!

As usual during the staging of the Summer Olympics, numerous...

Read More