Once, during a Super Bowl halftime interview, the legendary Jim Brown said that this man was the greatest running back he had ever seen. Former Detroit Lions and Pittsburgh Steelers head coach Buddy Parker said, “He’s like Jim Thorpe.”

When he’s running, he’s the best fullback in the business; that’s because he’s a great blocker. He does everything a great fullback should do.” Hall of Fame quarterback Bobby Layne said of him, “All I know is that he was a great football player; one of the greatest.”

Were they talking about Walter Payton? Brown was on the record as being an admirer of “Sweetness”. Maybe they were talking about Barry Sanders, a dynamic runner in his own right. Then again, they could have been casting their compliments the way of John Riggins, or Green Bay’s Jim Tayler.

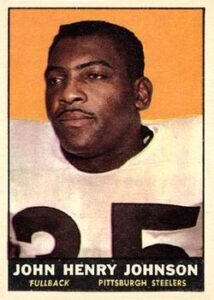

No, their admiration was meant for one of the toughest, meanest, most talented runners who was forgotten so quickly that the Pro Football Hall of Fame came close to completely overlooking him for induction. That man’s name is John Henry Johnson.

Today we’re celebrating the birthday of John Henry Johnso who was born on November 24, 1929, in Waterproof, Louisiana.

Johnson Combined Talent and Attitude

The advantage Johnson brought to professional football was his size to go with agility and speed. He was 6 feet 2 inches tall and anywhere from 210 to 230 pounds during his playing career.

Seeing John Henry coming directly at them was intimidating for opposing tacklers. If he wasn’t running over them, he’d make a lightning cut and utilize his breakaway speed to outrun them. His size also made Johnson one of the most intimidating blockers in the NFL.

Dick Hoak, his backfield mate with the Steelers, said about Johnson, “He was probably as good a blocking fullback as I’ve ever seen John Henry once said about himself, “I was a darn good blocker. I liked it. That’s the only way you can be a good blocker.

You’ve got to like blocking. It gave me a chance to hit guys and knock ‘em down, all those guys who did things to me. It gave me a chance for revenge.”

Hall of Fame quarterback Bobby Layne, who played with Johnson in Detroit and Pittsburgh said of him, “John Henry is my bodyguard. Half the good runners will get a passer killed if you keep them around long enough. But a quarterback hits the jackpot when he gets a combination runner-blocker like Johnson.

In an article for Sport Magazine in 1964, Layne listed Johnson as one of Pro Football’s 11 Meanest Men. He said, “By ‘mean’, I mean vicious, unmanageable, consistently tough. I don’t mean dirty.”

Of course, it was also Layne who said, “John Henry went three ways, Offense, defense and to the death.”

John Henry’s Road to the NFL

Johnson began flashing his athletic ability at Pittsburg High School in Pittsburg, California where he earned 12 letters in track and field and football. In his senior year he set a California high school record for the discus throw.

When it was time for college, Johnson stayed close to home, enrolling at St. Mary’s College in Moraga, Ca. At that time, St. Mary’s had a fairly strong football program that, in 1945, went to the Sugar Bowl, and in 1946, played in the second, and last, Oil Bowl in Houston.

In 1950, the school finished the season with a 2-7-1 record. An 84-yard kickoff return by Johnson led St. Mary’s to their 7-7 tie against the University of Georgia.

After the 1950 season, St. Mary’s dropped its football program so Johnson transferred to Arizona State. Despite the step up in college competition, Johnson continued playing halfback and fullback on offense, linebacker and safety on defense and on special teams returning punts.

In 1952, his final year of college eligibility, he led college football in punt returns.

Even though John Henry was finished with college football that season, he wasn’t finished with school. Johnson went back as time permitted and in 1955, earned his degree in education.

A Short Detour

In the 1953 NFL Draft, Johnson was chosen in the second round, 18th overall, by the Pittsburgh Steelers.

In 1952, Pittsburgh’s starting quarterback, Jim Finks, was second in the league in passing yards and tied with Pro Football Hall of Fame quarterback Otto Graham with 20 touchdown passes but the Steelers’ ground game was horrible.

The Steelers finished the 1952 season last in rushing yards and yards per attempt. Pittsburgh’s best back was Ray Mathews who rushed for 315 yards in 12 games with no touchdowns.

For whatever reason though, Johnson passed on the NFL and decided to sign with the Calgary Stampeders in the Western Interprovincial Football Union (forerunner to the Canadian Football League).

Because John Henry played multiple positions on offense and defense, like he had done in college, he didn’t lead the league in a specific category.

Johnson did rush for 648 yards on 107 carries, caught 33 passes for 365 yards, intercepted five passes, returned 47 punts and 20 kickoffs, completed five passes and scored eight touchdowns.

The Million Dollar Backfield

Like all other teams in the NFL by 1953, the San Francisco 49ers ran a T-formation offense, or full-house backfield, with three backs, a fullback and two halfbacks, lined up behind the quarterback, “breath” and theirs was arguably the best in the NFL.

Three-fourths of that backfield was in place by the time that San Francisco traded defensive back Ed Fullerton to Pittsburgh for the NFL rights to Johnson, who they immediately signed to play left halfback.

Fullback Joe Perry had been with the team since 1948, when the 49ers were still doing battle in the All-America Football Conference (a conference that we will talk about in a future time journey).

Quarterback Y.A. Tittle started his career in the AAFC with the Baltimore Colts. That team, along with the Cleveland Browns and the 49ers joined the NFL after that league folded after its 1949 season. Baltimore went bankrupt after the 1950 season. Because of that, Tittle joined San Francisco in 1951.

Right halfback Hugh McElhenny was selected by San Francisco in the first round, ninth overall, in the 1952 NFL Draft and was an explosive playmaker.

Perry finished the 1953 season as the league leader in rushing yards and rushing touchdowns. Both he and McElhenny were named First Team All-Pros and joined Tittle in the Pro Bowl.

With Johnson added for the 1954 season, the group meshed together so well and was of such worth to San Francisco that Dan McGuire, the team’s public relation man, dubbed them The Million Dollar Backfield.

As a runner, in his rookie NFL season, Johnson rushed 129 times for 681 yards and nine touchdowns. He also caught 28 passes for 183 yards and threw a 10-yard touchdown pass. He finished second in the NFL with 681 rushing yards, but it was in his work as a blocker where John Henry stood out.

Johnson paved the way for Joe Perry to run 173 times for a league leading 1,049 yards, a 6.1 yards per carry average. Hugh McElhenny ran 64 times for 515 yards, an 8.0 yards per carry average. For Perry, Johnson’s work clearing running lanes helped him became the first running back in NFL history to rush for 1,000 yards in consecutive seasons.

With all of that power on offense you would think that San Francisco crushed its competition on the way to the NFL Championship. Unfortunately, as dominant as their offense was, their pass defense was one of the worst in the league.

The 49ers finished 7-4-1, good for third place in the West Division behind the Detroit Lions and Chicago Bears.

The Twilight of the Hall of Fame Backfield

Unfortunately, that 1954 season was the Million Dollar Backfield at its peak. In 1955, Johnson injured his shoulder in San Francisco’s first game against the Los Angeles Rams and only played in seven games, starting three. He struggled to gain 69 yards in only 19 carries.

Without John Henry’s fierce presence at left halfback, San Francisco as a team only rushed for 1,713 yards and 12 touchdowns, after punching across 28 touchdowns in 1954. Perry led the team with 701 tough rushing yards.

In 1956, the 49ers were on their third head coach in three seasons and they moved away from the full house backfield that had made San Francisco the talk of the league.

Johnson was moved to fullback and shared time with Perry at the position. He played all 12 games, rushing 80 times for 301 yards and two touchdowns. San Francisco finished that season with a 5-6-1 record.

A Champion in Detroit

In May of 1957, Johnson was traded by San Francisco to the Detroit Lions for fullback Bill Bowman and defensive back Bill Stits.

Head coach George Wilson, who had replaced Buddy Parker when Parter resigned at the team’s training camp dinner, installed Johnson at fullback and he ran for 621 yards and five touchdowns to help lead Detroit to a share of the West Division title with, of all teams, the San Francisco 49ers. The Lions came from behind to win the playoff 31-27 to advance to the NFL Championship Game.

In that game, John Henry rushed 7 times for 34 yards, caught one pass for 16 yards and recovered a fumble in Detroit’s 59-14 smashing of the Cleveland Browns.

In 1958 and 1959, Johnson again struggled with injuries. His no-holds-barred playing style made him a ripe target for opponents to take shots against and he paid the price.

In 1959, a personal problem reared its head when a bench warrant was issued in California after his ex-wife claimed Johnson was behind in alimony.

On November 2, Johnson missed a team plane after a 33-7 loss to the 49ers in San Francisco. No explanation was given when Johnson reappeared and Wilson suspended him indefinitely. The relationship between the two was permanently broken.

The Pittsburgh Years

In the spring of 1960, Pittsburgh Steelers coach Buddy Parker, yes, the very same Buddy Parker, traded two undisclosed draft picks to the Lions to bring John Henry to Pittsburgh.

The most productive rushing years of Johnson’s career came during the six years he spent with the Steelers.

In 1962, John Henry became the first 1,000 rusher in Pittsburgh Steelers history, running 251 times for 1,141 yards and seven touchdowns.

Johnson was named second team All Pro after that season and made his first Pro Bowl appearance since 1954. He ran for over 1,000 yards again in 1964 and made his final Pro Bowl squad.

John Henry’s greatest game as a runner came in Week 5 of 1964 against the Cleveland Browns. He carried the ball 30 times for 200 yards and three touchdowns in Pittsburgh’s 23-7 victory. It was only the ninth time in NFL history that a runner had reached 200 yards.

Unfortunately for Johnson, Pittsburgh was rarely competitive in the six seasons that he played for them, only twice finishing above the .500 mark.

Career Finale

Johnson missed all but one game of the 1965 season, then signed with the Houston Oilers in 1966 to finish his career. He retired after his one season in the AFL.

Upon his retirement, Johnson was ranked fourth on pro football’s all-time rushing yards list, behind Jim Brown, Jim Taylor, and his fellow Million Dollar Backfield teammate Joe Perry.

For a long time, it appeared that the NFL might forget John Henry. He spent years after his retirement trying to get a job as a coach but was repeatedly passed over for jobs. Many times by former players with far less experience than he had.

Johnson experienced the same when he became eligible for the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1971. He made the finalist list for the first time in 1975. He continued a yearly appearance on that list through 1980 but while backs like Jim Taylor, Gale Sayers and Tuffy Leemans found the door wide open for them, John Henry was always on the outside looking in.

Finally, in 1987, the Senior Committee made Johnson the final member of the Million Dollar Backfield to be inducted.

Later Life in Decline

As Johnson entered his 50s, his family slowly noticed a change in how he was communicating. His thought processes began slowing. In 1989, John Henry was enrolled in an Alzheimer’s disease study where he received a formal diagnosis that he was suffering from the disease.

John Henry Johnson died on June 3, 2011, at the age of 81. His 49ers backfield partner Joe Perry had died five weeks earlier and both families donated their brains to the UNITE Brain Bank for study. He was diagnosed with stage 4 CTE, the most advanced stage of the disease.

I don’t want to end the story of John Henry Johnson on such a discouraging note though. He gave everything to professional football, the teams he played for and the teammates that he helped to excel. He always made an effort to give back to the communities where he played and his family loved and cared for him to the end.

That’s a more fitting epitaph for a man who lived his life refusing to be stopped.

Please Share If You Liked This Article

Please Note – As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases

More Posts From Pro Football Time Machine

John Henry Johnson and the Million Dollar Backfield

Once, during a Super Bowl halftime interview, the legendary Jim...

Read MoreJim Finks: A Builder of Winners

Jim Finks could have spent his life as the answer...

Read MoreDropping Back: Chuck Noll, Pittsburgh’s Man of Steel

Chuck Noll agreed to do one ad during his 23...

Read More