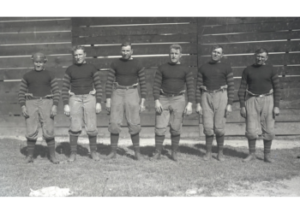

Back in the prehistoric days of professional football, a family of rugged, tough as steel brother, the Nessers, ruled pro football gridirons throughout the Midwest. The Nesser brothers competed against the celebrated pioneers of the game, including Jim Thorpe and Knute Rockne. The brothers held their own against all competitors, no matter their reputation.

Despite drawing thousands of fans wherever they played, the Nessers are practically forgotten today, especially in Columbus, Ohio, their home town.

This is the story of the Nesser brothers, forgotten pioneers of professional football and the NFL.

Who Were the Nesser Brothers?

There were eight Nesser brothers in total, along with four sisters. John was the oldest of the brothers, followed by Pete, Phil, Ted, Fred, Frank, Al, and Ray.

Pete was the only one who didn’t play football, even though he was reportedly the largest of the brothers, weighing 325 pounds. As for Ray, he was often photographed in uniform with the brothers for promotional purposes, but there’s little evidence that he played more than a handful of games.

Still, six Nessers on the field was a formidable force for any team of that era to face.

The brothers were dedicated to the game of football. They spent ten hours a day working as boilermakers in the Panhandle Shops of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The rest of their waking hours were devoted to practicing football.

The Panhandle Shops lined a seven-mile stretch of railroad connecting Ohio to Pennsylvania through the West Virginia panhandle. Along that route were multiple shops where train maintenance and repair were handled.

It was tough, strenuous work, but the brothers still made time for football. During their one-hour lunch break, they’d gulp down their meals so they could spend the remaining time running drills and plays on a field behind the rail yard. After work, there would be even more practice at a local park.

These hardened railroad men made an impact, most of the time literally, on opposing players, including legends of the early professional game. Jim Thorpe once said that he dreaded meeting Ted Nesser coming down the field more than any other player he ever faced.

Legendary Notre Dame coach Knute Rockne, who played in the Ohio League for four seasons, said of them, “Getting hit by a Nesser was like falling off a moving train.”

The Brothers on the Field

Each Nesser could play all 11 positions on the field, but each had unique talents.

Phil weighed in at 236 pounds and played tackle on both offense and defense.

John, the oldest brother, usually played quarterback, which wasn’t the glamorous position it is today. In the single-wing offense, the quarterback often lined up behind the guard and tackle to block on offense and was one of the primary tacklers on defense.

Ted was a star on every team he played for and often served as the coach as well. He was a smart football mind who originated many plays that later saw widespread use in both pro and college football. On the field, Ted usually played halfback and was a bruising ball carrier.

Fred was the tallest of the brothers at 6-foot-5 and weighed between 240 and 250 pounds. He was a formidable blocker at tackle and end, but he could also line up in the backfield and run over opponents. Fred was also considered a serious contender for the heavyweight boxing title, held by Jack Johnson until 1915 and then by Jess Willard, until a broken wrist ended his career in the ring.

Frank stood 6-foot-3 and weighed around 250 pounds. Despite his size, he was a fast and elusive runner. He was also an accomplished passer in a game played with a football that wasn’t designed to be thrown easily. On top of all that, Frank was a talented punter, placekicker, and dropkicker.

When the Panhandles played the Canton Bulldogs, Frank Nesser and Jim Thorpe would stage punt, pass, and dropkick competitions before the game. Both men could throw the ball more than 60 yards on the fly, but Frank was more accurate.

Both also regularly kicked the ball 50 yards and farther. In one game, Frank was credited with kicking a 63-yard field goal, again, with a ball that was designed to be carried and not much else.

Al had the longest career of all the brothers in the early NFL, not surprising, since he was the second-youngest sibling. Al played end and guard for more than 20 years and was never sidelined by injury, despite never wearing a helmet. Al Nesser was the last man in the National Football League to play without head protection.

Al once said, “I never bothered with the helmet. I thought it would interfere with my thinking. My personal opinion is that a man is more alert without one. Anyway, I depended on speed—and you can’t depend on speed and tonnage.”

Al wasn’t the only brother who went without a helmet. Fred, John, and Phil also played bareheaded.

Along with the Nessers, their brother-in-law, John Schneider, also played for the Panhandles.

A Landmark Moment

A landmark moment for the fledgling NFL came in 1921, when the league was still known as the American Professional Football League. Panhandles head coach Ted Nesser moved into the offensive line so his son Charlie would line up in the backfield.

It marked the first time in professional sports history that a father and son played for the same team and it’s the only time in NFL history. That achievement would go unmatched in major professional sports until 1973, when hockey legend Gordie Howe came out of retirement to play in the World Hockey Association with his sons, Marty and Mark.

The Nessers and the Panhandles

Ted Nesser was the first brother to be paid for playing football. In November of 1904, he traveled from Columbus to Shelby, Ohio, to play against the Massillon Tigers. The following week, Ted was lining up for Massillon. He played with the Tigers during each of their championship seasons from 1904 through 1906.

The year 1904 also marked the first time former Panhandle Shop machinist-turned-sportswriter Joe Carr attempted to start a team in Columbus centered around Ted Nesser and other Panhandle Shop players.

Carr had a dream that professional football could become more than a collection of rough, loosely organized teams. He envisioned football as a legitimate business that could one day rival Major League Baseball, the king of professional sports in the first half of the 20th century.

That initial Columbus team only played two games before folding due to financial difficulties. But Carr didn’t stay down long. In 1907, he formed a new team with the Nesser brothers as the main attraction. Five brothers played on that 1907 squad.

Carr also found creative ways to save money. He took advantage of the railroad’s policy allowing employees to ride trains for free and scheduled most of the team’s games on the road, eliminating stadium rental, promotion, and ticket-printing costs.

Because the team was constantly traveling, the Nessers became well known throughout Ohio League cities and across the Midwest. The downside was that, since they rarely played in Columbus, they were never as well known, or celebrated, in their hometown.

The Famous Nesser Brothers

The Nesser brothers were a major draw wherever they played, and they traveled to face the best teams available. Newspapers frequently highlighted their presence.

When the Panhandles traveled to Rock Island, Illinois, in November of 1916, the game was advertised as “The Famous Columbus Panhandles against the Rock Island Independents.” A crowd of 6,000 fans at Douglas Park watched the Independents win 40–0.

Another newspaper notice that same month read that opponents “…will try to avenge the early-season defeat by the famous Nesser combination.”

In November of 1917, the Fort Wayne Gazette announced that “The Columbus Panhandles, with the Famous Nesser Bros., oppose Friars Sunday.”

Even areas not yet caught up in pro football fever recognized the Nessers. In a feature story in the Los Angeles Evening Post on October 31, 1916, the lead sentence read: “Here they are, 1,477 pounds of brothers, the seven famous Nesser boys, professional football players, baseball players, and boxers.”

In 1916, the Panhandles traveled to Detroit to play the Heralds at Navin Field. Ticket prices were raised from $1 to $1.50, and they still drew 7,000 fans.

The Nessers put fans in the seats wherever they went, and Joe Carr never lacked opponents eager to schedule games against them.

The Nessers on the Field

Despite their talent and the punishment the team inflicted, Columbus never won an Ohio League championship. A major reason was Carr’s habit of scheduling the toughest teams throughout the Rust Belt to test his Panhandles squad against. Whether they won or lost, though, they usually won the battle of bruises.

The team’s best seasons came between 1914 and 1916, with records of 7–2, 8–3–1, and 7–5. Their inability to defeat Jim Thorpe’s Canton Bulldogs proved costly in 1915 and 1916.

The Panhandles fell to 2–6 in 1917, losing to powerhouses such as the Canton bulldogs, Akron Pros, and Massillon Tigers. The Ohio League did not play in 1918, as many players enlisted or were drafted, following the United States’ entry into World War I.

The 1919 season marked the final chapter of the Ohio League.

Birth of the NFL

In August of 1920, representatives from Canton, Cleveland, Dayton, and Akron met in an effort to control salaries and prevent players from jumping between teams. On September 17, 1920, they met again, this time with seven additional teams, to form the American Professional Football Association.

Joe Carr was not present at that meeting, but the Panhandles were admitted to the league shortly afterward. Likely because the other team owners understood the importance of having a man of Carr’s experience and business acumen as part of the league.

Frank, Phil, and Ted, who also served as head coach, were listed on the 1920 Panhandles roster, while Al had moved on to play guard for the Akron Pros. In Akron’s first game, against the Wheeling Stogies, Al recovered three fumbles and returned them all for touchdowns.

The Panhandles are credited with playing in the first APFA game on October 3, 1920, losing 14–0 to the Dayton Triangles. The following week, they faced Al and the Akron Pros, losing 27–0.

Al continued to star for Akron and played a major role with the Pros as they finished the 1920 season 8–0–3 to earn the league’s first championship.

The End of an Era

Time catches up with every dynasty, no matter the sport. By 1921, age and nearly two decades of smashmouth football had caught up with the Nessers.

The Panhandles finished 2–6–2 in 1920, with their wins and ties coming against, semi pro, non-league competition. They were struggling to compete against the younger talent in the new league, even with Ted as player/coach and Frank, Phil and John Schneider still anchoring the team.

In 1921, after the Panhandle’s final win to finish 1-8, John, Ted, Fred, and Phil retired from professional football. John, at age 46, held the NFL record as its oldest active player for 53 years until George Blanda broke it in 1974.

Frank played in 1922, then returned with Columbus, by then renamed the Tigers, in 1925 and 1926, the final year for professional football in Columbus.

Al starred with Akron, Cleveland, and the New York Giants, winning an NFL Championship with New York in 1927, his second, and finished his career in 1931.

Joe Carr left the Panhandles after the 1920 season and became president of the APFA in 1921. He oversaw the name change to the National Football League and directed and guided the league’s growth until his death in 1939. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963 and remains the only Panhandle honored there.

The Nessers and the Hall of Fame

As for the Nesser brothers, why haven’t they been enshrined in the hall, or even considered for enshrinement, despite their level of play on the gridiron and attention that they brought to professional football before the founding of the NFL?

One likely issue is the football careers of the Nesser brothers, except for Al, were close to finished at the time of the new league’s founding. As for Al, he played at a high level for years in the early NFL but he’s still been ignored for Hall of Fame consideration.

Also, in the era that the Nesser’s played in, and for many years after, college football was considered the pinnacle of the sport. Despite their fame, the Nessers and the Panhandles were overshadowed by the college game. especially in Columbus, where, in 1922, Ohio State opened The Horseshoe, a top facility for fans to watch football games.

The Panhandles’ lack of a true home field, combined with Carr’s road-heavy scheduling, contributed to the brothers fading from local memory.

The brothers have also been a victim of recency bias. It’s a pronounced problem here in the present day, see Ralph Hay and Lavvie Dilweg, but also an issue when the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s charter class was being selected.

Based on voting patterns since the class of 2020, where 20 nominees entered the hall to celebrate the NFL’s 100th anniversary, it appears that the selection committee feels that there is nobody else from the league’s infancy needing induction.

Only one player in The Hall’s charter class took the field in pro football’s prehistoric age, Jim Thorpe. An article published by the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2013 said of Thorpe, “He was the first big-name athlete to play pro football and essentially put the game on the map.”

Nobody will ever argue against Thorpe’s legendary status, especially me. Thorpe, as a world class athlete, playing for the Canton Bulldogs brought needed attention to professional football. He’s earned the recognition that he has received including the statue of him, in classic running pose, at the entrance to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

However, the Nesser brothers deserve recognition for the part they played in building the base of fans throughout the Midwest, western Pennsylvania and along Lake Erie into New York that the fledgling NFL was able to tap to support the league through its early years.

It’s time for this family of hard working, football loving railroad men to receive the Hall of Fame recognition they deserve.

What Can Be Done? A Call to Action!

A movement is underway to support the enshrinement of the Nesser brothers.

I encourage readers of this article to follow “The Nesser Brothers for Hall of Fame” on Facebook, a page established by the Nesser family in September of 2024 to bring attention to the brothers, highlight their accomplishments and generate support for their enshrinement.

There is also a way to take a direct role in nominating the Nessers for Hall of Fame enshrinement. Fans can nominate any Player, Coach or Contributor who has been connected with pro football simply by writing to the Pro Football Hall of Fame at:

2121 George Halas Drive NW, Canton, OH 44708.

The hall receiving tangible notifications of support for the Nesser brothers is sure to raise their profile among the selection committee members.

Remember the names: John, Phil, Ted, Fred, Frank, and Al. They excelled at the sport they loved for close to two decades and, enshrined in the Hall of Fame or not, deserve recognition from all football fans for their contributions in growing the popularity of pro football and launching the league that became the NFL.

Please Share If You Liked This Article

Please Note – As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases

More Posts From Pro Football Time Machine

John Henry Johnson and the Million Dollar Backfield

Once, during a Super Bowl halftime interview, the legendary Jim...

Read MoreJim Finks: A Builder of Winners

Jim Finks could have spent his life as the answer...

Read MoreDropping Back: Chuck Noll, Pittsburgh’s Man of Steel

Chuck Noll agreed to do one ad during his 23...

Read More